India - US Defence Deal 2020: The Strategic Dimension

Quote from Dr Zafar Iqbal Cheema on 9th May 2020, 8:32 am

India - US Defence Deal 2020: The Strategic Dimension

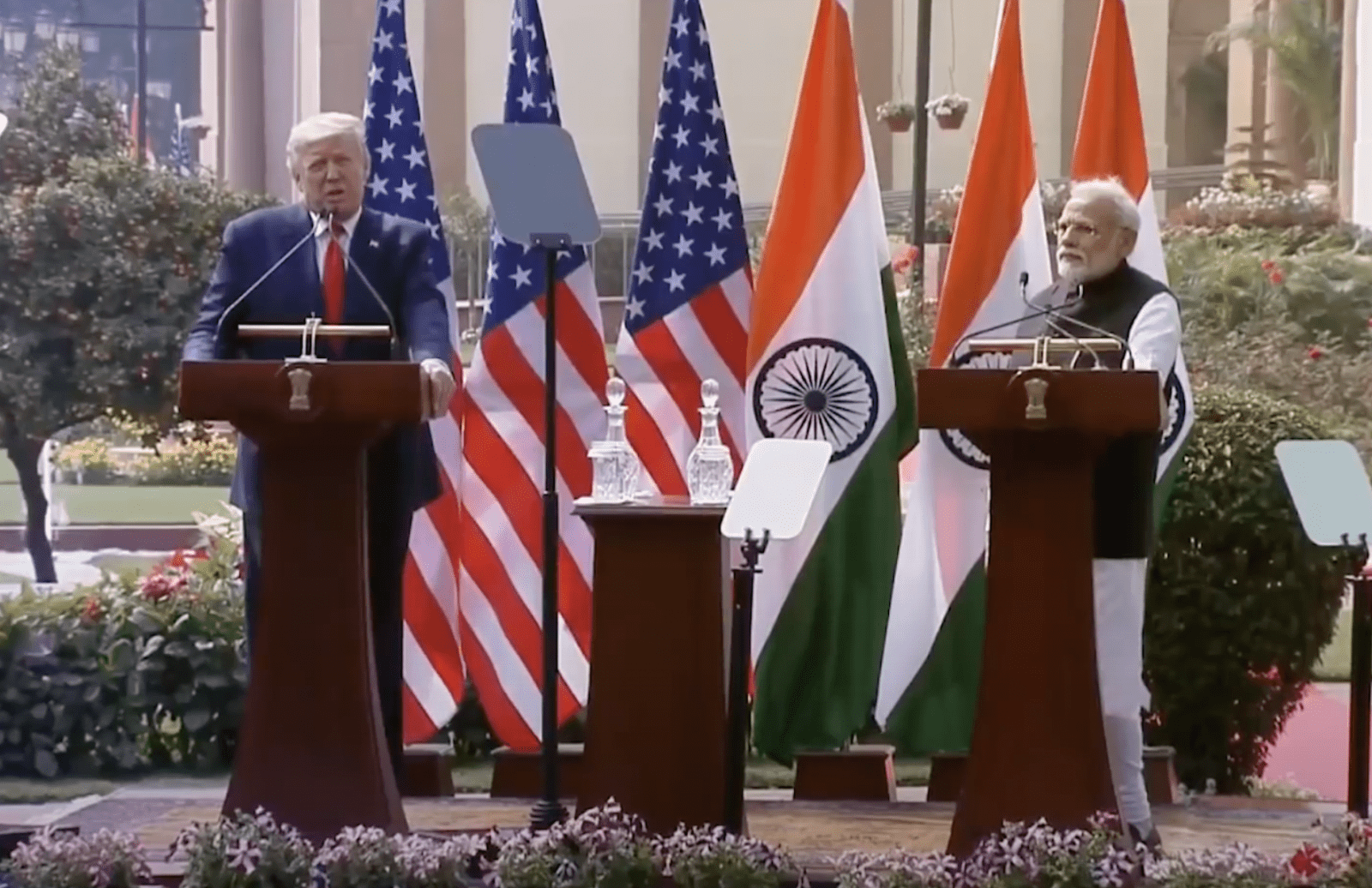

India – United States Defence Deal signed during President Donald Trump’s visit to New Delhi in February 2020 is yet another milestone in the Indo-US Strategic Partnership whose concrete development coincided with the beginning of 21st century. Former President Obama’s prognostic statement that the 21st will be the Asian century was less of forecast than indicating the US preference between the rising Sino-Indian giants and about India as the Pivot of the US Asia Pacific strategy. The origin of India-US embrace lies deeper in the history than what seems at the surface of their politico-diplomatic relations. In the early 1950s, the US made preemptive purchases of strategic raw materials from India under the Battle Act 1951 (officially known as Mutual Defence Assistance Control Act 1949) to forestall the prospects of the burgeoning Indo-Soviet relations but could not quite succeed. India was unwilling to join the Cold War whose dynamics withheld the Indo-US embrace until the end of the 1990s. In the aftermath of 1962 India’s China War that brought profound changes in the fissures of international politics, the US provision of military assistance to India clearly demonstrated, as indeed it did reiterate through the post-1965 war arms embargo, that Pakistan’s security is not its first and only priority.

There is no denying the fact that the recent Indo-US Defence Deal carries serious long-term consequences for Pakistan. It’s not just the $3 billion financial worth of the deal and state-of-the-art weapon systems that matter alone but the doctrinal intent behind the provision of specific arms. 24 MH-60R Seahawk helicopters from the inventory of the US Lockheed Martin may add significantly to the anti-submarine warfare capabilities of the Indian Navy, but according to the US-India joint statement, the helicopters will “advance shared security interests, job growth, and industrial cooperation between both countries.” Again, the provision of six AH-64E Apache attack helicopters for the Indian Army is not a decisive increment but it is the overcoming of traditional US reluctance to share specific technologies from military perspective that matters more from the Indian viewpoint. The concomitantly agreed sale of 10 AGM-84 L air-launched Harpoon missiles along with 16 MK 54 Lightweight Torpedoes to be integrated into the P-8I aircraft, though not being seen as a ‘game changer’, but will place the highly advanced technology in Indian hands, which Pakistan Navy has so far been holding to its chest as a superior weapons system that it alone possessed in South Asia and about which there have been serious considerations to be employed in a special role.

The deployment of these weapon systems, as stated in the US–India joint statement, will not only ‘advance shared security interests’, in the Indian Ocean region and in the vicinity of the Arabian/Persian Gulf, but will also be a sort of Sword of Damocles hanging over the head of security of Pakistan’s naval vessels. India already possessed sophisticated military systems of Russo-Soviet origin, but the acknowledged technological superiority of US systems will enhance the lethality of the Indian Navy in submarine warfare and anti-ship capabilities. It’s not that Pakistan has no deterrent against such weapon systems, but it will endanger the sense of security that has somewhat existed in the field of conventional military conflict below the nuclear threshold. It will also enhance the existing disparities in the conventional asymmetries between India and Pakistan whose military equilibrium strongly favours India and add further strain on Pakistan’s employment of nuclear deterrence.

It’s ironic that the Indo-US Defence Deal has been concluded at a time when Pakistan enjoys very warm political relations with the United States and its widely believed to be ruled by a staunchly pro-US, if not a protégé, regime of Premier Khan whose constituent politico-military membership includes career professionals who are famous to be longstanding US clients. On the Afghanistan front, concerning Taliban–US negotiations for the withdrawal of foreign troops, Pakistani regime is ostensibly making unilateral concessions to the US and is alleged by the critics to be bent over backwards to promote US interests, despite the latter’s direct engagement in the providing weapon systems to India, which are highly detrimental to the Pakistan’s military/security interests. It’s a contemptuous disregard, not only to regional strategic stability, but also to the growing conventional military asymmetry in the region in continuously providing the types of latest weapon systems and military technologies to India that in the immediate future can only be used against Pakistan and has no conceivable employment against China. Pakistan looks hamstrung to develop credible options due to its engineered economic collapse.

The deal is part of a larger objective to develop regional military superiority in the Indian Ocean and Indo-Pacific regions. The United States and India seem to be working on the assumption that there is a link between CPEC and Sino-Pakistan naval military collaboration in the Indian Ocean Region for which China is providing its advanced military hardware to boost Pakistan’s naval military capabilities around Gwadar. The conundrum is complex and complicated enough to delink the various dimensions of maintaining conventional and strategic equilibrium from Sino-Pakistan’s perspectives and US engagement in strategic cooperation with India.

India has acquired the distinction of becoming world’s second-largest importer of arms over the past five years, and for the very first time, has been ranked third in top global military expenditure list with a 6.8 % rise in its annual global military spending in 2019, and with a 3.7 % share in the global military expenditure for that year. India’s massive arms buildup, aggressive conventional military capabilities and preemptive nuclear posture are directly threatening strategic stability in South Asia, which otherwise is not the proclaimed US objective.

India - US Defence Deal 2020: The Strategic Dimension

India – United States Defence Deal signed during President Donald Trump’s visit to New Delhi in February 2020 is yet another milestone in the Indo-US Strategic Partnership whose concrete development coincided with the beginning of 21st century. Former President Obama’s prognostic statement that the 21st will be the Asian century was less of forecast than indicating the US preference between the rising Sino-Indian giants and about India as the Pivot of the US Asia Pacific strategy. The origin of India-US embrace lies deeper in the history than what seems at the surface of their politico-diplomatic relations. In the early 1950s, the US made preemptive purchases of strategic raw materials from India under the Battle Act 1951 (officially known as Mutual Defence Assistance Control Act 1949) to forestall the prospects of the burgeoning Indo-Soviet relations but could not quite succeed. India was unwilling to join the Cold War whose dynamics withheld the Indo-US embrace until the end of the 1990s. In the aftermath of 1962 India’s China War that brought profound changes in the fissures of international politics, the US provision of military assistance to India clearly demonstrated, as indeed it did reiterate through the post-1965 war arms embargo, that Pakistan’s security is not its first and only priority.

There is no denying the fact that the recent Indo-US Defence Deal carries serious long-term consequences for Pakistan. It’s not just the $3 billion financial worth of the deal and state-of-the-art weapon systems that matter alone but the doctrinal intent behind the provision of specific arms. 24 MH-60R Seahawk helicopters from the inventory of the US Lockheed Martin may add significantly to the anti-submarine warfare capabilities of the Indian Navy, but according to the US-India joint statement, the helicopters will “advance shared security interests, job growth, and industrial cooperation between both countries.” Again, the provision of six AH-64E Apache attack helicopters for the Indian Army is not a decisive increment but it is the overcoming of traditional US reluctance to share specific technologies from military perspective that matters more from the Indian viewpoint. The concomitantly agreed sale of 10 AGM-84 L air-launched Harpoon missiles along with 16 MK 54 Lightweight Torpedoes to be integrated into the P-8I aircraft, though not being seen as a ‘game changer’, but will place the highly advanced technology in Indian hands, which Pakistan Navy has so far been holding to its chest as a superior weapons system that it alone possessed in South Asia and about which there have been serious considerations to be employed in a special role.

The deployment of these weapon systems, as stated in the US–India joint statement, will not only ‘advance shared security interests’, in the Indian Ocean region and in the vicinity of the Arabian/Persian Gulf, but will also be a sort of Sword of Damocles hanging over the head of security of Pakistan’s naval vessels. India already possessed sophisticated military systems of Russo-Soviet origin, but the acknowledged technological superiority of US systems will enhance the lethality of the Indian Navy in submarine warfare and anti-ship capabilities. It’s not that Pakistan has no deterrent against such weapon systems, but it will endanger the sense of security that has somewhat existed in the field of conventional military conflict below the nuclear threshold. It will also enhance the existing disparities in the conventional asymmetries between India and Pakistan whose military equilibrium strongly favours India and add further strain on Pakistan’s employment of nuclear deterrence.

It’s ironic that the Indo-US Defence Deal has been concluded at a time when Pakistan enjoys very warm political relations with the United States and its widely believed to be ruled by a staunchly pro-US, if not a protégé, regime of Premier Khan whose constituent politico-military membership includes career professionals who are famous to be longstanding US clients. On the Afghanistan front, concerning Taliban–US negotiations for the withdrawal of foreign troops, Pakistani regime is ostensibly making unilateral concessions to the US and is alleged by the critics to be bent over backwards to promote US interests, despite the latter’s direct engagement in the providing weapon systems to India, which are highly detrimental to the Pakistan’s military/security interests. It’s a contemptuous disregard, not only to regional strategic stability, but also to the growing conventional military asymmetry in the region in continuously providing the types of latest weapon systems and military technologies to India that in the immediate future can only be used against Pakistan and has no conceivable employment against China. Pakistan looks hamstrung to develop credible options due to its engineered economic collapse.

The deal is part of a larger objective to develop regional military superiority in the Indian Ocean and Indo-Pacific regions. The United States and India seem to be working on the assumption that there is a link between CPEC and Sino-Pakistan naval military collaboration in the Indian Ocean Region for which China is providing its advanced military hardware to boost Pakistan’s naval military capabilities around Gwadar. The conundrum is complex and complicated enough to delink the various dimensions of maintaining conventional and strategic equilibrium from Sino-Pakistan’s perspectives and US engagement in strategic cooperation with India.

India has acquired the distinction of becoming world’s second-largest importer of arms over the past five years, and for the very first time, has been ranked third in top global military expenditure list with a 6.8 % rise in its annual global military spending in 2019, and with a 3.7 % share in the global military expenditure for that year. India’s massive arms buildup, aggressive conventional military capabilities and preemptive nuclear posture are directly threatening strategic stability in South Asia, which otherwise is not the proclaimed US objective.