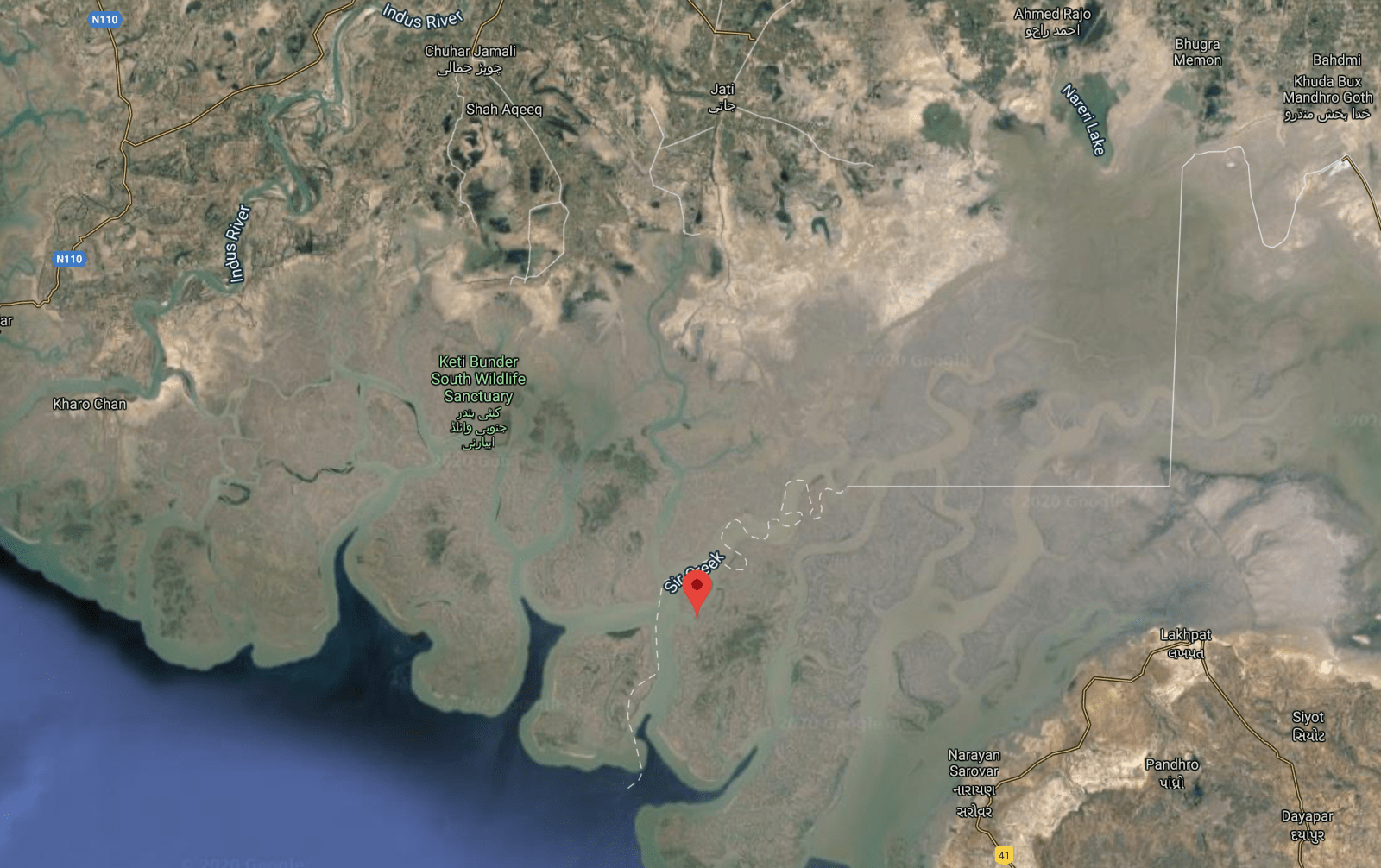

While Pakistan and India are involved in a plethora of disputes, like Kashmir and Siachen, the Sir Creek issue has the propensity for a solution. Sir Creek, a 100 nautical mile strip of water between the state of Gujrat in India and the province of Sindh in Pakistan, has also kept the two countries at loggerheads for decades. The issue like many others is a legacy of the undermarketed tracts at the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. Sir Creek is a marshy strip in the Rann of Kutch area lying between the southern tips of Pakistan’s Sindh province and Indian state of Gujarat, opening in the Arabian Sea. The dispute is related to the Rann of Kutch. During the Partition of India in August 1947, Pakistan inherited the control of the whole of northern Rann of Kutch, but India occupied a part of it in 1956 to promote its grandiose plan of establishing a major naval base at Kandla in the Gulf of Kutch, linking it with Rajasthan and adjacent states via an array of rail and roads, backed by military garrisons contiguous to the Pakistani border.

While Pakistan and India are involved in a plethora of disputes, like Kashmir and Siachen, the Sir Creek issue has the propensity for a solution. Sir Creek, a 100 nautical mile strip of water between the state of Gujrat in India and the province of Sindh in Pakistan, has also kept the two countries at loggerheads for decades. The issue like many others is a legacy of the undermarketed tracts at the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. Sir Creek is a marshy strip in the Rann of Kutch area lying between the southern tips of Pakistan’s Sindh province and Indian state of Gujarat, opening in the Arabian Sea. The dispute is related to the Rann of Kutch. During the Partition of India in August 1947, Pakistan inherited the control of the whole of northern Rann of Kutch, but India occupied a part of it in 1956 to promote its grandiose plan of establishing a major naval base at Kandla in the Gulf of Kutch, linking it with Rajasthan and adjacent states via an array of rail and roads, backed by military garrisons contiguous to the Pakistani border.

Pakistan’s concerns led to ministerial-level talks that only recognized the dispute, but brought no solution, resulting in a skirmish in April-May 1965. The threat of a wider conflict was thwarted by the then British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, who arbitrated a ceasefire from 01 July 1965.

The dispute, referred to the India-Pakistan Western Boundary Case Tribunal, presided by Swedish Judge Gunnar Lagergren, awarded a solution in February 1968 that was accepted by both contestants. The adjudicated boundary stopped short of Sir Creek because neither had requested for the demarcation of this tract. Pakistan believed it had inherited the solution provided in the Bombay Resolution of 1914 when Sindh was a part of the Bombay Presidency of British India and Kutch was ruled by Rao Maharaj.

The 1914 resolution that awarded the whole of Sir Creek to Sindh, which in 1947 joined Pakistan while Gujarat opted for India, should have been respected. The matter would have been amicably resolved, but two developments changed the Indian stance: firstly, the prospect of oil and gas being found in the Sir Creek area and secondly, the advent of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of Seas (UNCLOS) to which both Pakistan and India became signatories. The consequent Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) granted Pakistan and India rights under the convention over the sea resources up to 200 nautical miles in the water column and up to 300 nautical miles in the land beneath the column. Resultantly, the position of both the countries hardened, since the EEZ congruent to Sir Creek is not only rich in marine life but may also contain sub-surface energy deposits and comprises rich nourishment resources at the sea bottom.

The solution to the Sir Creek issue lies in the adoption of the Bombay Government Resolution of 1914, which demarcated the boundaries between the two territories, included the creek as part of Sindh, thus setting the boundary line known as the “Green Line” or the eastern flank of the creek.

India contests Pakistan’s claim, stating that the boundary lies mid-channel of the Creek. In its support, it cites the Thalweg Doctrine in International Maritime Law, which states that river boundaries between two states may be divided by the mid-channel if the water-body is navigable. India claims it to be navigable, while in reality, the creek itself is located in the uninhabited marshlands that get flooded during the monsoon season, making it partially navigable then. If the boundary line is demarcated, according to the Thalweg principle, Pakistan stands to lose a considerable portion of the territory that was historically part of the province of Sindh. Acceding to India’s stance would also result in the shifting of the land/sea terminus point several kilometres to the detriment of Pakistan, leading, in turn, to a loss of several thousand square kilometres of its EEZ.

Another factor is that the position of the water body is shifting and hydrographers by both sides confirmed that the latest position favoured Pakistan. Maritime and international boundaries once fixed, cannot be repositioned on the basis of shifting ground positions of water bodies. India insists that the maritime boundary be determined first, which is illogical until the Sir Creek issue is resolved. India should be urged to accept the readymade solution on the basis of the Bombay Resolution of 1914 or seek third party arbitration, as it did in the case of Indus Water Treaty of 1960 or the 1968 Rann of Kutch Commission.

Today, owing to a surge in commercial activities in sea trade, such as shipping and extraction of natural resources, the laws of the sea hold utmost importance in international law. The scope of modern sea laws have gone well beyond defining states’ national coastal territories and tend toward the protection of trade, environment, and maritime zones in its contents. This evolution of the law faces emerging contemporary challenges in governing maritime legal issues, such as defining the EEZs and national jurisdictions along disparate coastal lines and unclear low-water marks or baselines.

History is replete with examples, where similar cases have been heard and resolved, while some remain disputed. One such case, the Anglo-Norwegian Fisheries case, was brought in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 1951 to define the legitimacy of straight baselines along coasts. This case later helped to develop the intricate rules defining baselines along coasts under the Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC). The world has since seen armed conflicts over the demarcation of baselines in this way; for instance, Libya and United States faced off in armed conflict over the demarcation of straight baselines along coastal lines in Libya. Furthermore, complications in marking these baselines are further complicated when marking baselines along river mouths and fringe islands. Moreover, Thailand, which has the world’s largest number of islands, is currently counting its islands again to revise its baselines along its coasts, in order to enjoy the privileges of internal waters and resolve the conflicting interests of its neighbouring countries. Similarly, the US is currently seeking to challenge China’s straight baselines in the South China Sea coastal areas, which were claimed by China in 1996.

More interestingly, the boundaries of the disputed Sir Creek do not only provide a massive fishing resource; the successful delimitation of borders in accordance with Indian desires will reduce the area of Pakistan’s EEZ by 2,246 resource-rich square kilometres. This fact is a substantiation of how a generous demarcation of baseline can affect maritime jurisdiction and the interests of neighbouring states. Besides this, Pakistan applied the straight baseline technique to demarcate its coastal areas in 1996; the United States contested the legitimacy of this demarcation in 1997. However, recently, in 2015, the United Nations Commission agreed to Pakistan’s extension of the seabed territory from 200 nautical miles to 350 nautical miles, such that Pakistan’s continental shelf would enjoy a further 50,000 square kilometres of seabed territory. So, arguably, since the UN has approved the demarcation of maritime zones of Pakistan, and since the United States alone challenges every nation’s baseline without particular interests, demarcation by Pakistan using straight baselines can be argued to be legitimate boundaries. In order to establish and comprehend excessive state practices of boundary demarcations at sea, it is essential to define the legal framework of the laws governing the demarcation of baselines and understand all maritime zones and national boundaries of coastal states. It is hoped that the Sir Creek issue may be amicably resolved thus.

Be the first to comment