Regular elections in Afghanistan are a right step towards flourishing democracy. While Doha peace process between the Taliban and the US is almost ready to bear fruit, the intra Afghan dialogue is a prerequisite for durable peace in the country. Ethnic divide based elections has ruined the basic foundations a prosperous society. It’s the high time that neighboring countries play a positive role in peace and conflict resolution of Afghanistan. It’s possible once democratic institutions are strengthened, civil society is developed and international community urges on free and fair elections.

Regular elections in Afghanistan are a right step towards flourishing democracy. While Doha peace process between the Taliban and the US is almost ready to bear fruit, the intra Afghan dialogue is a prerequisite for durable peace in the country. Ethnic divide based elections has ruined the basic foundations a prosperous society. It’s the high time that neighboring countries play a positive role in peace and conflict resolution of Afghanistan. It’s possible once democratic institutions are strengthened, civil society is developed and international community urges on free and fair elections.

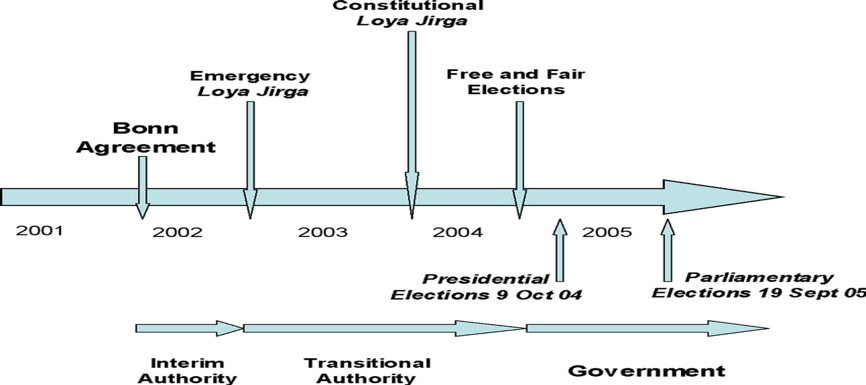

Mainstreaming Democracy in Afghanistan. In 2001, under the United Nations Security Council’s ‘Agreement on Provisional Arrangements in Afghanistan Pending the Re-Establishment of Permanent Government Institutions’ Afghanistan ushered on the path of democracy. Dubbed as the ‘Bonn Agreement’ though brokered by the UN, was the brainchild of the US that paved way for a political road map for the conflict-ridden country. Continuous nine days closed door negotiations led to the signing of Bonn Agreement. The agreement excluded the outgoing Afghan head Mr. Rabbani and Taliban. As per the agreement, Afghanistan went through a drastic change with Mr. Hamid Karzai being selected as the interim head of state and a three-year political and administrative plan for the formulation of state institutions. The aim of the agreement was to endorse Afghanistan’s future political processes and institutions of governance based on ‘the right of the people of Afghanistan to freely determine their own political future in accordance with the principles of Islam, democracy, pluralism and social justice’ (United Nations Security Council, December 2001). The Bonn Agreement was followed by an Emergency Loya Jirga (grand council) in 2002 that laid the foundation for transitional government, the ratification of 2004 Afghan constitutional framework, the 2004 and 2005 presidential and parliamentary elections. The following image provides a pictorial overview of the process:

Fig 1: Bonn Agreement ( Source: https://doi.org/10.1080/02634930600902991)

Despite the fact, that the Bonn Agreement introduced the notion of democracy it failed to create a state that could not uphold its legitimacy outside Kabul. Rather it harbored a tribal set up divided on ethnic lines.

Afghan Presidential Election and the Supreme Law of the state. 502-member assembly in Kabul approved the constitution of Afghanistan on 4th January 2005. The constitution created both an Islamic and democratic state. It provided for a Presidential system of government based on the US model. Power is divided between the President, Supreme Court, National Assembly and the Grand Assembly. Articles 60, 61 and 62 in chapter three of the constitution of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan enunciate the eligibility of Presidential candidates. Under the aforesaid articles the President:

- Shall be the head of state of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, executing his authorities in the executive, legislative and judiciary fields in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution. The President shall have two Vice-Presidents, first and second. The Presidential candidate shall declare to the nation names of both vice-presidential running mates. In case of absence, resignation or death of the President, the first Vice-President shall act in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution. In the absence of the first Vice-President, the second Vice-President shall act in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution. (Art 60)

- Shall be elected by receiving more than fifty percent of votes cast by voters through free, general, secret and direct voting. The presidential term shall expire on 1st of Jawza of the fifth year after elections. Elections for the new President shall be held within thirty to sixty days prior to the end of the presidential term. If in the first round none of the candidates gets more than fifty percent of the votes, elections for the second round shall be held within two weeks from the date election results are proclaimed, and, in this round, only two candidates who have received the highest number of votes in the first round shall participate. In case one of the presidential candidates dies during the first or second round of voting or after elections, but prior to the declaration of results, re-election shall be held according to provisions of the law. (Art 61)

- The individual who becomes a presidential candidate shall have the following qualifications:

- Shall be a citizen of Afghanistan, Muslim, born of Afghan parents and shall not be a citizen of another country;

- Shall not be less than forty years old the day of candidacy;

- Shall not have been convicted of crimes against humanity, a criminal act or deprivation of civil rights by court.

No individual shall be elected for more than two terms as President. The provision of this article shall also apply to Vice-Presidents. (Art 62)

Moreover, the Afghan Electoral Law came to force in 2016. Articles 38, 44 and 45 of the constitution lay down the rules for the requirements, restrictions and election for the presidential process. The new Independent Election Commission (IEC) of Afghanistan has delayed election twice due to a number of obligations and reforms. The major obligation is the prevalence of technology in the polls to curb fraud and rigging. In addition, the commission is in the process of overcoming the challenges it faced during the 2018 parliamentary election and the need for new commissioners. Also, for conducting timely election, IEC requires budgetary support both from the government and international donors.

On the IEC’s constant delays and President Ashraf Ghani’s tenure expiration on 22nd May 2019, the Supreme Court of Afghanistan intervened and announced a breakthrough decision in his favor thus extending his presidential term until election. The constant delay and extension of President Ghani’s tenure was unwelcomed by opposition groups. Mehwar-e- Madom-e- Afghanistan, Grand National Coalition, Independent Commission for Overseeing the Constitution, the civil society called the delay and decision unconstitutional and a clear violation of article 61. However, this is not the first time the Afghan government has faced the legitimacy question. A precedent was set in the years 2009 and 2014, when Kabul experienced a similar situation. Subsequently, the Supreme Court extended the term of the then President Mr Hamid Karzai.

Afghanistan is a nascent democracy; the aforementioned constitutional and electoral statutes are a prerequisite for its democratic growth. If article 61 is not followed, this may lead to the notion of “Political Dictatorship”. Time and again, the Afghan parliament and judiciary have failed to maintain a democratic order. Keeping in consideration the sanctity of the constitution, the Afghan polity need to strengthen and protect the constitution.

Overview of Elections in Afghanistan since 2001. The 2001 US invasion of Afghanistan led to the overthrowing of the Taliban regime and advent of democratic norms in the country. The process of a political settlement began with Bonn Agreement 2001 and continued through 2014 US brokered National Unity Government.

Afghanistan witnessed its first ever Presidential Election on 9th October 2004. A total of 18 candidates filed nomination papers for the country’s top job. Primary contenders were Hamid Karzai, Yunus Qanoni, Rashid Dostum and Muhammad Mohaqiq. It is noteworthy that the major candidates for 2004 presidential polls belonged to four distinct ethnicities: Karzai of Pashtun clan, Qanoni of Tajik faction, Dostum of Uzbek group and Mohaqiq of Hazara community. As an intrinsic response, Afghans rooted for their ethnic representative.

Ethnicity had an explicit impact on the election outcome. As a result, Karzai became the first elected president of the country with 55.4% (Afghanistan Presidential Election Result, 2004) of the total votes in his favor. This presidential poll deliberated that “historical ethnic patterns have long driven conflict dynamics in the county. No candidate received significant support outside of their particular ethno-linguistic group” (Johnson, June 2006). Despite the security concerns, the first election was a momentous victory in the face of insurgents. 70% of registered voters practiced their basic right and out this percentage 40% (Afghanistan Presidential Election result, 2004) were women. This is by far the highest recorded voter turnout in the history of democratic process of Afghanistan.

Amidst insurgency, fraud and media ban, Afghanistan conducted its second presidential poll on 20th August 2009. A total of 32 candidates contested for presidentship. Leading candidates were Karzai, Dr. Abdullah and Ramazan Bashardost. Ethnic dynamics continued during the electoral process leaving afghan voters divided between Pashtuns, Tajiks and Hazaras. Karzai garnered 49.67% (Afghanistan Presidential Election Result, 2009) of the vote while Dr Abdullah emerged as a runner up with 30.59% votes. Since Karzai’s winning percentage was below the required constitutional percentage i.e. 50%, therefore, a runoff vote was held between Karzai and Dr Abdullah. However, Dr Abdullah withdrew his candidature at last minute. Eventually, Karzai was declared as president-elect. Though Karzai won the election for the second time, there were widespread rigging allegations against him. The Electoral Complaints Commission invalidated One third of Karzai’s votes. As compared to previous election, voter turnout was fairly low. According to IEC preliminary result announcement, voter turnout was 38.7 % (IEC Press Release, September 16, 2009).

The third presidential election was conducted in a post conflict set up on 5th April 2014. A total of eight candidates participated in the race for the of the president. Outgoing President Karzai was ineligible to run for the third term. Top rivals were Dr Ashraf Ghani and Dr Abdullah. In the first round of voting, Dr Abdullah gained a leverage of 45% (Afghanistan Presidential Election Result, 2014) votes over Ghani who came in second place with 31.5%. Both the candidates failed to cross the 50% vote threshold; hence, a second voting round was conducted. Ghani emerged as a leading candidate garnering overwhelmingly high number of votes in the second round. 55.6% of votes determined his victory over Dr Abdullah (Reuters. 2016, Feb 24th). Abdullah and his supporters refused to accept the result and alleged that Ghani’s campaign had committed massive ‘electoral fraud’. The issue of rigging is not new to the electoral process of the country. Nevertheless, the 2014’s electoral outcome of first and second rounds showed disparity that was objectionable. The situation turned ugly when Abdullah and his supporters threaten to take to streets. Amidst the anarchic picture, International players led by US and UN intervened at highest level to negotiate a political settlement. US former Secretary of State John Kerry brokered a compromise deal by forming the ‘National Unity Government’. Under the deal, Ghani was given the office of the president while Abdullah was offered an unconstitutional position of Chief Executive officer.

The difference between 2014 and the previous two presidential polls is twofold. 2014 election marked a smooth transition of power from a long reigning president to a new president and administration. Besides, three of the four leading candidates in 2014 polls were Pashtuns. This support the notion of Afghans voting on the basis of ethno-linguistic lines that further led to a sudden swing from the first election to the runoff in favor of Dr Ghani.

Good Governance and Elections in Afghanistan. The state of good governance in Afghanistan is frail. The concept itself is quite “westernized” to the cursory democracy. There are no visible indictors of good governance in the Afghan set up and has rarely been evaluated. Consequently, there has been an absence of transparency, administrative principles, accountability and rule of law. In addition, after the fall of Taliban in 2001 the democratic governments have failed to formalize good governance. The war-torn country has confronted a myriad of challenges, however, the notion of consolidating the country’s nascent democracy has always been at rear.

A free, fair and transparent election is a prerequisite of good governance in a country. True representatives of the people remain committed to the development and prosperity by their long term pragmatic policy goals and their implementation. The Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan was established in 2006 under article 156 of the constitution of Afghanistan. It has a well-structured hierarchy and is headed by a chairperson who is appointed by the President. The IEC looks after policy making i.e. credibility of elections, oversight of IEC secretariat, logistics and technical aspects of polls. IEC being an independent institute has time and again experienced interferences by the government, which has in turn given rise to doubt.

In February, President Ghani sacked the country’s IEC. The commission failed to announce 2018’s parliamentary polls result thus overshadowing transparency. Seven new election commissioners were appointed along with Ms Hawa Alam Nuristani, first woman chair in the history of IEC. The UN Security Council report on Afghanistan enlisted a number of reasons for the postponement of elections i.e. reconstitution of the electoral management bodies, the new provisions in the amended Election Law and the delays in finalizing the parliamentary election results (UNSC report, 2019 June 14).

A major part of IEC finance is borne by the Afghan government, the UN Electoral Support Project and the international community. IEC chair Ms. Nuristani confirmed the electoral budget. September 2019 polls will cost $149 million, out of which $90 million will be paid by the afghan government (Shaheed, 2019). Technical, logistics and security flaws are manifold. Election observers and opposition candidates are skeptical about the ability of IEC to conduct timely and transparent polls. A recent study conducted by the Free and Fair Election Foundation of Afghanistan (FEFA) and Transparent Election Foundation of Afghanistan (TEFA) have summed up a number of core issues as follows:

- Lack of interest from the international community towards the electoral process;

- The election commission’s “failure” to drop fake names from voter list;

- Ambiguity about the use of biometric devices in the elections;

- The nature of relations between the election commission and the government.

Against the backdrop of the ongoing intra- Afghan dialogue, the presidential election has been plagued by constant delays for the last four months. Recently the Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan has re-scheduled the electoral process to 28th September 2019. The upcoming election will prove a turning point for the fragile democracy; however, the transition is highly dependent on the peace deal.

Though US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has reflected optimism. While addressing media last month in Doha, Pompeo told reporters that US was hopeful to negotiate a peace deal with Taliban before 1st September (DW, 2019). Even the Taliban have given a very positive posture about the success of negotiations in Doha. Speaking to Al Jazeera, the Taliban’s political spokesman in Doha, Suhail Shaheen, said the US and the Taliban were finalising the agreement during the ninth round of negotiations. He further said that the deal would see the US and other foreign forces gradually withdraw from Afghanistan in exchange for a commitment by the Taliban that the country will not be used as a launch-pad for global attacks.

After the two sides agree on the two central issues, a separate dialogue on ensuring a permanent ceasefire and a power-sharing agreement between the Afghan government and the Taliban are expected to take place in the form of intra-Afghan talks. So far, the Taliban has refused to speak to the Afghan government, calling it a “puppet regime” of the West. The group says any engagement with Kabul would grant the government legitimacy (Aljazeera, 2019). Only a possible political settlement will pave way for peace between Taliban and Afghan government, provided IEC fulfills its duty of conducting timely polls.

The Next Candidates. The Independent Election Commission published a preliminary list of presidential nominees on 5th February 2019. The list includes 18 candidates out of whom the strongest rivals are, incumbent President Ghani, chief executive Dr Abdullah and former national security advisor Muhammad Hanif Atmar. In contrast to 2004 and 2009 elections, there are no female candidates.

Dr. Abdullah, a Noorzai Pashtun belonging to Kabul was one of the top finishers’ of 2014 polls. He has entered the presidential race for the third time and challenging Ghani for the second time. In the past he has served as foreign minister under Northern Alliance government and President Karzai. Due to his one-time relation with the late Ahmed Shah Masood (leader of the anti- Taliban Northern Alliance), he is infamous among the group. His electoral slogan is Subat wa Hamgerayi (Stability and Integration). Despite his mixed Pashtun-Tajik ethnicity, he’s seen by many as a Tajik. For the upcoming polls he has garnered support from Uzbek and Hazara leaders i.e. Abdul Rashid Dostum (leader of Junbish party) and Karim Khalili (Wahdat party) (Kumar & Noori. 2019, January 20). In addition, Jamiat-e- Islamic party has announced their support in favor of Dr Abdullah. His first and second running mates both belong to the minority groups of Uzbeks and Hazara, thus his vote bank will balance in between Tajik, Uzbek and Hazara constituencies.

The coming months are crucial for President Ghani’s administration, who is in the race of seeking the country’s top job yet again. His five-year presidency is tainted with hesitant decisions, which resulted in upsetting the ethnic minorities at home. For example, the firing of senior advisor Mr. Ahmed Massoud, sending home the governor of Balkh province General Noor Muhammad (both belonging to Tajik clan) and the forced exile of Mr. Abdul Rashid Dostum sparked tensions amongst the already ethnically divided country.

Moreover, President Ghani is accused of appointing a number of Pashtuns to his administrative team in Kabul as the election is nearing. Pashtuns make up 42 % of the afghan population and represent a greater political say (2018, June 7). President Ghani, a native Pashtun himself could not do well at the domestic front reason being that the non-Pashtun community though in minority, were placed at powerful positions in the past five years. Apart from that, he has failed miserably to engage the Taliban in intra- afghan dialogue. In spite of that, President Ghani has shown remarkable progress at the international front. As Ayoobi, EK. (2018, Feb 6) stated that President Ghani has time and again raised voice against state sponsored terrorism implying towards Pakistan, at regional and global forums. This has mustered him a bad name in the Pakistani polity where Ghani rejected a friendly hand extended.

Ghani is also very openly favoring India in comparison to Pakistan. Instead of keeping his country away from the cold war between any two rivals, Ghani has preferred India over Pakistan. He has also revamped Afghanistan’s position in regional mechanism, e.g. SAARC, Heart of Asia- Istanbul Process, etc. Hence, he tried to promote the country as a key economic link between South and Central Asia.

On the other hand, Supreme Court of Afghanistan in a breakthrough decision extended President Ghani’s tenure until September election. President Ghani, an Ahmadzai Pashtun is one of the top contenders for the presidential race. His slogan is Dawlat-sazan (State-builders), however he was unable to live up to that during his tenure. Belonging to a strong Pashtun background and having worked in the World Bank and United Nations, it was expected of him to bridge the ever-widening ethnocentric gap. (Contsable, P. 2019) states that, “President Ghani has attempted to build a reputation as a reformist technocrat, economic visionary, democratic modernizer and champion of peace. But his efforts have been undercut by entrenched poverty and violence, especially the deadly Taliban campaign that has persisted despite the presence of thousands of U.S. troops, many of whom may now be withdrawn by President Trump. Ghani has also suffered from his image as an impatient and isolated leader who only trusts a few aides.”

On the contrary, former national security advisor Mr. Hanif Atmar, a Durrani Pashtun hailing from Laghman province has emerged as a powerful contender. Atmar has played a significant role in the country’s political ambit. He is well connected with the grass root level. He has worked as a humanitarian worker in Pakistan’s refugees camp in 1990’s. He has earned the title of ‘negotiator’. He is well known in the Taliban circle and ever since then he has kept open channels with them under various government assignments. In one telling episode, whenever former President Karzai invited Taliban negotiators, messengers, and leaders for negotiations in Kabul, they would meet Atmar for advice and assistance.

In addition, he practiced shuttle diplomacy while in National Security office. He would often shuttle between the office of the President and the office of the Chief Executive to settle their differences and call for unity (Asey, 2019). Apart from that, he is largely credited for the 2014 Bilateral Security Agreement with USA and the 2016 peace deal with Hizb- e –Islami. In addition, Joshi, P. (2018, December 21) asserts that Atmar has built a corruption-free and trustworthy image at home and abroad. That will in turn prove to be significant in convincing foreign donors primarily the US government to continue supporting Afghanistan’s reconstruction programs. Besides, he has served in authoritative positions as minister for rural development and rehabilitation in President Karzai’s government from 2002-2006, education minister (2006-2008), interior minister (2008-2010) and as national security adviser (2014-2018) under President Ghani.

Like Dr Abdullah’s running mates, Atmar has proposed a Tajik and a Hazara for first and second vice- presidentship. His election slogan Solh wa Etedal (Peace and Moderation) is based on his unique attributes of unity, inclusivity, pluralism and conciliator. USA and western powers look forward to a leader with Atmar’s skills in Kabul, who shall be able to forge the country’s political future and deliver to the people of Afghanistan.

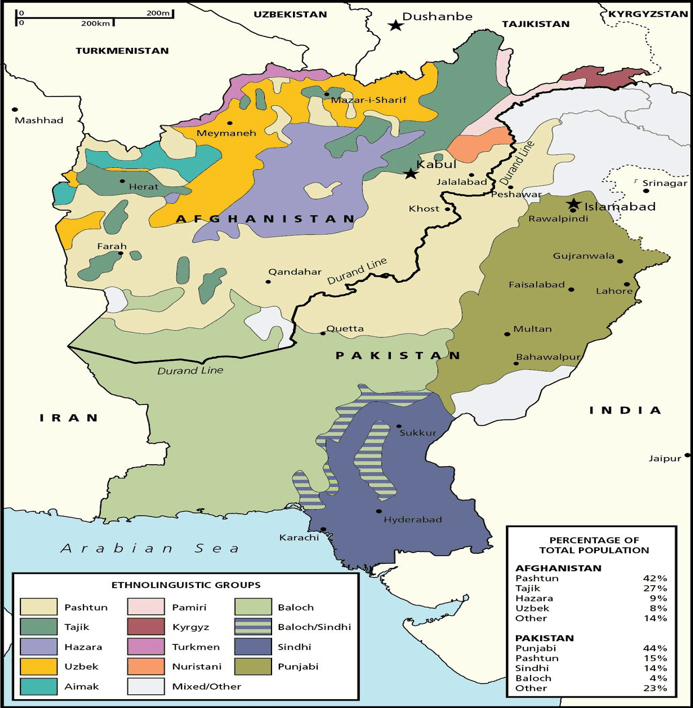

Ethnic Politics and Afghan Elections. Afghan politics and its electoral process is always influenced and marred by ethnic division. It is an ethnically heterogeneous country of 35.3 million population ( World Bank, 2017). Four major ethnicities namely Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks and Hazaras represent the majority population of the country. Pashtuns make up to 42%, Tajiks 27%, Hazara 9% and Uzbek 8%.

Source: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/maps/afghanistan-and-pakistan-ethnic-groups/

The last census was conducted forty years ago. There is an absence of credible data in context of exact proportion of ethnicities. This has led to each group claiming to represent the largest faction of the population. Over the time, ethnic card has been politicized and unconsciously ingrained in the country’s social fabric.

Since the inception of modern-day Afghanistan, Pashtuns have enjoyed the center-stage. Much of afghan history is narrated from a Pashtun lens. They have been favored and given tokens of privileges in all sectors. Tajiks were left with the economic sector and the educational institutions, whereas the Hazaras were marginalized in general. The different treatment of the people went along with the forming of ethnic stereotypes: Pashtuns were considered ‘bellicose’, Tajiks were said to be ‘thrifty’, Uzbeks were known as ‘brutal’ and the Hazaras as ‘illiterate’ and ‘poor’ ( Schetter. 2003, June). However, it is noteworthy that Pashtuns with 42% representation are in plurality not majority. This plurality is often misperceived for their greater say in the political sphere of the country.

Ethnicity is used as an instrument for political demands. Leaders of these ethnic groups stress on economic and political resources disparity. They often tell their followers that survival of their “own ethnic group” is of utmost importance and that their interests have to be safeguarded from “other ethnic groups”. Tajiks blame Pashtuns; Pashtuns have ill feelings for Tajiks and so on. Since resources are concentrated in Pashtun provinces and controlled by Pashtun leaders in Kabul, the north- south dialogue has exacerbated ethnic patterns. This has further engendered jealousy amongst various groups and tarnished the true essence of nation-hood. Clan politics is prevalent in the country. Often the contesting candidates garner support from tribal heads, who are naturally dominant in their respective tribes.

For the upcoming polls, presidential candidates are covertly using the ethnic card for legitimizing their political existence. Dr Abdullah Abdullah has the support of Tajiks, Atmar has the backing of Pashtuns, Hazaras and Uzbeks while Ghani is standing on Durrani Pashtuns pillar. This shows that the Pashtun votes will be divided between Atmar and Ghani. This will give a numerical edge to Dr Abdullah. Ethnic dynamics is embedded in the afghan society and will continue to play a significant role in the political process.

Role of Women in Afghanistan’s Elections. For a budding democracy like Afghanistan, the challenge of inclusivity looms large. Universal and equal suffrage as a basic human right is the core of a functioning democracy. The term universal suffrage enunciates the right of every adult to participate in electoral processes regardless of gender, race, religion or any other characteristic. However, the notion of universal suffrage is subject to local traditions in a post-conflict Afghanistan.

Until 1996, women in the country experienced liberty. They were allowed to flourish in education, social and economic spheres. Women were in politics, but they were barred of contesting elections. During the Taliban rule, there was a complete suppression of women’s participation in social life. They were confined to homes and were ordered to observe parda. Under the Taliban rule, women were effectively excluded from public life entirely (Goodwin. February 1998).

The Afghan women breathed a sigh a relief after the fall of Taliban in 2001. In 2000 “Declaration of the Essential Rights of Afghan Women” came into being when 300 afghan women gathered in Tajikistan to formulate a document to end the misery of women in Afghanistan resulting in active participation in electoral process. Later in 2003, President Karzai incorporated the declaration into domestic law. The women rights law lessened the gender gap on paper.

Under the 2004 constitution of democratic Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, an attempt was made to re-introduce women participation. Increased participation of women in government is enshrined in articles 83 and 84 of the Afghan constitution. As per these articles, 68 seats out of a total of 250 are reserved for women in Wolesi Jirga. While 17 seats out of 102 are reserved for women in Mashrano Jirga. The statute encouraged women inclusion and representation nevertheless, oppression and discrimination did not completely diminish.

In current scenario women in Afghanistan have remarkably progressed. With the assistance of international donors and the gradual change in local perception, afghan women are able to step outside their houses and participate in democratic development. There are barriers but it is noteworthy that they conjured up courage to make their presence felt at formal levels.

The country’s three presidential polls witnessed only three female presidential candidates. In 2004, Dr Masooda Jalal stood for the office of the president. She was the only woman among 18 presidential candidates. She received 1.1% of total vote and female voters’ turnout was an overwhelming 40%. Though she lost but a precedent was set for afghan women. This was exemplified in 2009, when two female candidates namely Shahla Atta and Dr Frozan Fana sought presidency. In 2014, the role of women as candidates and voters was marginalized than in previous elections. The only female candidate Khadija Ghaznavi was disqualified by Independent Election Commission from an initial list of registered candidates. IEC had declined to explain the disqualification.

The country’s fourth presidential election scheduled for September has no female candidate. The situation is worrisome for the viability of democracy in Afghanistan. Women are the pillars of a democratic society and they cannot be secluded in any way. If seclusion practices continue, the essence of a robust civil society fades. In Afghanistan’s case, cultural norms, patriarchy and insurgency remain dominant factors in hindering women empowerment. In addition, women often refrain from contesting on general seats. It is difficult for women to contest as independents in elections as they have to bear the burden of security threats, nomination fee and resources for campaigns. With 48.45% of female population, and with a feeble democracy, women’s refraining from contesting general elections is worrisome for the future political process of Afghanistan.

The aforementioned female presidential candidates are a trio of trailblazers in a post conflict Afghanistan. They are an inspiration for women in other developing democracies in the region, as well as in western democracies. It is interesting to note that Pakistan has only had one female head of government and the U.S has never had a female president. The opportunity now exists in Afghanistan for women to have representation in the parliament, which will validate their participation and diminish patriarchal beliefs in Afghanistan (McQuire, 2015).

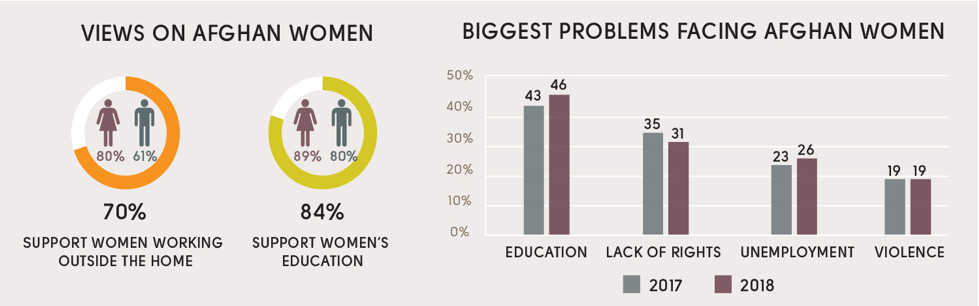

Since the fall of Taliban in 2001, women slightly showed signs of improvement and emancipation. With the 18 years of conflict coming to an end, Afghan women still struggle with numerous challenges daily. Key findings from the Asia Foundation’s 2018 survey on Afghanistan are listed as follows:

- 70% afghans agreed that women should be allowed to work outside the home.

- 84% afghans favored that women should have the same opportunities as men in education.

- Almost half of respondents (46%) cite illiteracy and lack of educational opportunities as the biggest problem facing Afghan women in 2018-19 electoral process.

- The level of support for the cultural practices of baad and baddal continues to decline and support for women in leadership positions—apart from that of the President—has increased marginally.

Despite the country’s numerous struggles, Afghans have manifested optimism. They strongly believe in democratic development as the only solution for Afghanistan’s future. From the above findings it is clear that the people of Afghanistan wish to see their women as empowered and dignified individuals of the society. Besides, attitude of afghan men towards women remain favourable.

Source: Survey of the Afghan People 2018: Asia Foundation

Women rights hold an important position on the agenda of intra- afghan dialogue. The mainstreaming of Taliban in the political ambit has drawn skepticism from various afghan factions. Afghans fear the same humiliation they faced under the seven years rule of Taliban during 1990s. This has led Afghan women and the International community to demand preservation of women rights from the Taliban. Last month in Doha, 50 afghan delegates including 10 women participated in the intra afghan dialogue.

The delegates attended the dialogue in personal capacities. The women delegates raised their concerns with Taliban. Ms Fawzia Koofi, women rights activist and a female delegate at Doha dialogue last month enquired the definition of ‘Hijab’ from Taliban. A Taliban representative responded accordingly: “From our understanding of Islam, the scarf wrapped around your head is what defines how women should be covering up. We don’t have a problem with that. But if Afghan women prefer wearing a burqa, which is part of the Afghan tradition, we don’t have a problem with that too” (Qazi, 2019 July). The reply connoted flexibility in the Taliban’s stance. Women inclusivity does not mean merely having female faces at the negotiating table. They have to be listened to and their demands must be given due heed. Both the Afghans and the international community negotiating with Taliban should ensure that a future agreement safeguards women’s right and social participation. Also, an enforcement mechanism has to be in place to uphold the provisions of an anticipated ‘peace settlement’ in case the Taliban backslide.

Afghan negotiators’ Better Alternate To a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) viz a viz women is clear-cut, Taliban have relatively softened their stance. In case of violation of women’s rights, the international community will impose financial sanctions. Most donors view women’s issue as a salient indictor of Afghanistan’s post-2001 democratization process. Without these donors, the country will be unable to maintain financial solvency (Ahmadi. 2019, March). To end, a future peace settlement has to honor the invaluable role of afghan women in social, political and economic realms of the country.

Pakistan: A frontline state once again. Conflict, peace agreement or elections in Afghanistan; Pakistan has been at the center stage of regional politics since 9/11. Given Pakistan’s proximity to Afghanistan and the former as a frontline state against global war on terror, it has suffered colossal losses. The bilateral relation has been tumultuous, primarily owing to trust- deficit. In the past five years, President Ghani tried time and again to bridge the gap between both the countries. However, Islamabad missed the opportunities. And when Islamabad extended olive branch, Kabul missed it due to its cordial relations with Pakistan’s archrival, India. Last July, in his inaugural speech, Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan stressed on revamping the country’s foreign policy. He highlighted that Pakistan would put in all efforts to bring an end to the Afghan conflict and promote bilateral economic relations. Keeping in consideration past strained relation and the upcoming presidential polls, Islamabad anticipates an inclusive and moderate power-sharing government in Kabul. For this purpose, it is robustly relying on soft means of diplomacy by supporting Doha peace negotiations.

Apparently, it is for the first time that Pakistan’s civil-military equation is on the same page in its policy towards Afghanistan. Islamabad, to its advantage, has influence over Taliban. This influence will turn out positive, if Islamabad brings both the Taliban and the Afghan government to the table. In order to facilitate a smooth transition of power in September 2019, Pakistan has to play a decisive part in making the Afghan Peace Process a success. In July 2019, President Ghani’s visit to Pakistan has been seen by many as an ice-breaker. The agenda of visit had three tiers namely trade and economy, health and repatriation of Afghan refugees. However, the highlight of Ghani’s visit was intra- afghan dialogue. In his reelection bid, Ghani intends to sell to the Afghan voters the success of a potential peace deal with the Taliban (Kakar, July 2019).

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s interests in Afghanistan are twofold. Firstly, the heightened rhetoric of curbing Indian influence in Kabul. Imrana Begum in her book ‘The Legacies of the Afghan- Soviet War in Pakistan’ asserted that Pakistan’s military was aware of the country’s geo-strategic position, it’s close ties with Pashtuns of Afghanistan primarily with the Taliban, made it a frontline state in the region for any US success in Pakistan. Had Pakistan not cooperated with US in the war on terror, besides other hazards, it would have enhanced India’s regional hegemony. Pakistan’s policy viz a viz Afghanistan has always remained India-centric. Vanda Felbaba- Brown has further highlighted this in her research paper on ‘The Predicament in Afghanistan’, Pakistan’s military and intelligence services have always stressed on minimizing India’s influence in Afghanistan.

Nevertheless, both the Prime Minister and Foreign Office of Pakistan have rejected the theory of strategic depth. Foreign Minister Quershi in Lahore Process stated that, ‘’Pakistan remains firmly committed to a peaceful, stable, united, democratic and prosperous Afghanistan. We are determined to build our bilateral relationship on the principles of non-interference, mutual respect and common interest” (Qureshi; 2019, June 23rd). Interference in Afghanistan has had a ripple effect on Pakistan.

Secondly, Islamabad is mending its relations with Washington viz a viz Taliban. Pakistani government has to stay vigilant and should not end up as Trump’s scapegoat in the region. Kakar asserted that in international politics, it is only realistic to not put all eggs in one basket. Relying too much on Taliban has done more harm than good to Islamabad. Promotion of Afghan reconciliation process should continue as it is in Pakistan’s interest. However, Islamabad has to let go of ‘dualism’ policy, the more it distances itself from Taliban the more it will win over Afghans. This will in turn engender cooperation and trust-building between both the countries. However, in Doha process, Pakistan being the immediate neighbor of Afghanistan has maintained a neutral stance. Last month Prime Minister Imran Khan on the occasion of President Ghani’s visit asserted that, “there is no blue-eyed of Pakistan among the candidates for the presidential election in Afghanistan and it is up to the people to choose their leader’’ (Abrar; 2019, June 24).

Conducting free and fair elections in Afghanistan is an uphill task. Although the past three presidential elections ensured a democratic transition of power however, the electoral processes were plagued by fraud, massive rigging, poor management and security threats. Samuel Huntington in his Political Order and changing societies paper demonstrated that, “what is the reason of political instability and violence in these countries? … rapid social change and the rapid mobilization of new groups into politics coupled with the slow development of political institutions” (1968, p.4). For this reason, instability in conflict ridden countries like Afghanistan is the lack of development of institutional arrangements.

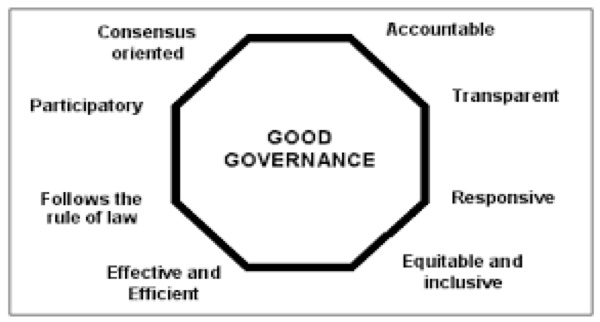

The concept of “Good Governance” is missing in Afghanistan’s political realm. Good governance is epitomized by predictable, open and enlightened policy making, a bureaucracy imbued with professional ethos in furtherance of the public good, rule of law, transparent processes and a strong civil society participating in public affairs. Characteristics of good governance are shown in the following image:

Source: What is Good Governance? unescap.org

In order for the upcoming presidential polls to be an instrument of peace-building, the following are key recommendations:

- Political leadership has to be re-defined. In a post- conflict set up a political leader ought to determine the future of reconstruction efforts. For this purpose, a charismatic leader is the need of the hour. One who is often identified in times of crisis and exhibit exceptional devotion in his field, as well as possessing a clear vision and the ability to engage with a large audience.

- Political parties have to discard the ethnic card and promote an inclusive environment. Political power is often accumulated in the hands of Pashtuns in Kabul. Peripheral provinces and non-Pashtun communities have to be equally represented in center.

- The constitution of Afghanistan has to be respected and followed accordingly. 2014 power-sharing fiasco paved way for political rivalry and created problems for the already divided country.

- Simultaneously, the country’s judiciary shall refrain from meddling in the political affairs. The extension of Karzai’s and Ghani’s tenures have invited criticism from the opposition factions.

- Last census was conducted in 1979, nearly 40 years ago. An accurate latest census will prove helpful for the country’s elections particularly voter registration process.

- Afghanistan has been a recipient of billions of aid for electoral programs. However, corruption remains rampant. International donors need to keep a check on the utilization of aid.

- Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan needs structural reconstruction. Electoral and secretariat staff ought to be trained for their duties. During elections international and local election observers shall closely note their performance.

- Independent Election Commission shall formulate a gender-working group. Through this group female voter turnout awareness campaign can be conducted and ensured.

- Security is a grave concern for the country. In order to re-enter the political arena Taliban have to reciprocate a peaceful and safe election.

The Afghan presidential election 2019, is a watershed for the international and the regional arenas. International and regional powers have invested in state-building efforts in post- Taliban Afghanistan. Nevertheless, these powers have to realize limitations of their capability. Brown (2013) explains that “externally driven state-building efforts can succeed and have succeeded. But the time and resource requirements for interveners are very large. It is comparatively easy for interveners to destroy a regime. It is harder for them to build a new political and economic order……..They can only assist in the state building effort. The ownership of and commitment to the effort must come principally from the local population” (p.174). With the peace dialogue underway and growing instability at home, an inclusive leadership in Kabul is the need of hour. In order to avoid a political vacuum a smooth transition of power has to be ensured for a strong, assertive and conflict- free Afghanistan.

References

Abrar, M. (2019, June 24). Pakistan to remain neutral in Afghan election, says PM. Retrieved from https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2019/06/23/pakistan-to-remain-neutral-in-afghan-election-says-pm/ ( 2019, July 5)

Qazi, S.(28 Aug 2019). US and Taliban ‘close’ to a peace deal: Afghan group’s spokesman, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/08/taliban-close-peace-deal-afghan-group-spokesman-190828114246759.html (Accessed on 30th August, 2019)

Ayoobi, EK. (2018, February 6). Ashraf Ghani: ‘Philosopher king’ or ethnonationalist? Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/ashraf-ghani-philosopher-king-ethnonationalist-180201144845423.html ( 2019, July 4)

Afghanistan in 2018: A survey of the Afghan People. Asia Foundation. https://asiafoundation.org/publication/afghanistan-in-2018-a-survey-of-the-afghan-people/

Asey, T. ( 2019, February 2019). Will This Man Be Afghanistan’s Next President? Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/will-this-man-be-afghanistans-next-president/ Viewed on 18th July 2019.

Begum, Imrana. (2018). The Impact of the Afghan-Soviet War on Pakistan. Oxford University Press.

Brown, Felbab Vanda. ( 2013). The Predicament in Afghanistan. In Brown Seynom & Scales H Robert (Ed), US Policy in Afghanistan and Iraq Lessons and Legacies (p. 174). New Delhi: Viva Books Private Limited.

Constitution of Afghanistan. www.afghanembassy.com.pl/afg/images/pliki/TheConstitution.pdf

Constable, P. (2019, January 20). Afghan president and 14 rivals launch race for July elections. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/afghan-president-and-14-rivals-launch-race-for-july-elections/2019/01/20/bf002466-1c9f-11e9-8e ( 2019, July 4)

Electoral Law (2016). Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/86577/97848/F592478731/AFG86577%20English.pdf (2019, July 12th)

Ethnic Groups of Afghanistan. (2018, June 7). Retrieved from https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/ethnic-groups-of-afghanistan.html ( 2019, July 6)

Goodwin, J. (1998, February 27). Buried alive afghan women under the Taliban.

Huntington, S. (1968). Political Order in Changing Societies (p.4). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hussain, K. (2019, August 1). Trump’s Smile. Islamabad, Dawn Newspaper.

Johnson, H Thomsan. (2019). The Myth of Afghan Electoral Democracy: The irregularities of 2014 Presidential election. Kabul, Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies.

Karzai’s winning percentages (2004 & 2009 election results). Retrieved July 17th 2019 from http://www.iec.org.af/prs/

Kakar, F. (2019, July 14th). A new beginning. Islamabad, The News.

Koepke, B. ( 2013, September). Iran’s Policy on Afghanistan: The evolution of strategic pragmatism. Sweden, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Kumar, R. & Noori, H. (2019, January 20). Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah face off again for Afghanistan presidency. Retrieved from https://www.thenational.ae/world/asia/ashraf-ghani-and-abdullah-abdullah-face-off-again-for-afghanistan-presidency-1.815788 ( 2019, July 5)

Mehmood, K. (2019, June 23rd ). Theory of strategic depth a dead horse. https://tribune.com.pk/story/1998421/1-theory-strategic-depth-dead-horse-says-qureshi/ Viewed on 30th July 2019.

Qazi, S. ( 2019, July 8th ). The activists leading efforts for women’s rights at Afghan talks. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/07/women-leading-efforts-female-rights-talks-taliban-190708113429836.html Viewed on 17th July 2019.

Saif Ullah, M. (2019, June 28th ). Why is the Afghan Peace Process not moving beyond Talks? https://www.dw.com/en/why-is-the-afghan-peace-process-not-moving-beyond-talks/a-49389958-0 Viewed on 20th July 2019.

Schetter, C. (2003). Ethnicity and the political reconstruction in Afghanistan. London School of Economics and Political Science. Available in LSE Research Online: June 2010.

Shaheed, A. (2019, July 14th ). Nuristani Says Govt, Donors Have Assured to Fund Elections. Tolo News. https://www.tolonews.com/elections-2019/nuristani-says-govt-donors-have-assured-fund-elections Viewed on 20th July 2019.

Smith, J. ( 2016, August 24th ). Commission releases disputed 2014 Afghan election results. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-election/commission-releases-disputed-2014-afghan-election-results-idUSKCN0VX1O8 Viewed on 21st July 2019.

UNSC,opcit. Ref 3, p.2.

UNGASC report. ( 2019, June). https://undocs.org/en/S/2019/493 (accessed on 17 July 2019)

World Bank demographics. (2017).

Be the first to comment