Introduction

General Chris Donahue’s departure from Hamid Karzai International Airport in late August 2021 marked a historic moment as the United States ended its two-decade war in Afghanistan. US intelligence agencies had believed that Kabul would fall within 90 days. The world was in shock when the Taliban took control of the capital within ten days on 15th August 2021, without resistance or bloodshed.

In Afghanistan, one community was concerned about the overwhelming power of the Taliban: the Afghan Hazaras. The Dari/Persian-speaking residents of the Turkish-Mongolian ethnic group, the third-largest ethnic group in the country who make up around 20% of the total Afghan population, had good reason to be worried when government officials fled the state and the Taliban took over the system. Almost two months after the Taliban takeover, on October 8, at least 72 Hazaras were slain at Kunduz’s Sayed Abad Mosque; this was followed by a suicide attack in Kandahar’s Bibi Fatima Mosque, which killed 63 people. The recent attacks on Hazaras make them fear an onset of genocide and ethnic cleansing, as they have long experienced institutional discrimination and marginalisation, social isolation, and direct violence. Historically marginalised, persistently discriminated against, and culturally varied, the Hazaras continue to be victims of extrajudicial killings, kidnappings, and disabilities orchestrated by the Taliban and other extremist groups. Hazaras are not only a target of the Taliban and other extremist organizations but have also been treated unjustly by previous Afghan governments.

The discriminatory behaviour of success Afghan governments towards Hazaras is evident at the political and economic levels. The latter have been oppressed since the 1800s, but the blueprint for internal colonialism was evident during Taliban rule in the 1990s. The purpose of this study is to examine the circumstances that the Hazaras experienced from the 19th century until Taliban rule in the late 1990s, as well as during the period of international intervention from 2001 onwards. The paper juxtaposes internal colonialism with direct violence against the Hazaras and how this can impact the current Taliban regime. Divided into different timelines from 1890 to 2020, it explains how the Hazaras were internally dominated by the core of Kabul, politically, economically, socially, and with massacres of minorities through direct violence.

Framework of Internal Colonialism

Internal colonialism seeks to explain the inferior situation of ethnic groups within the confines of a larger state ruled by other ethnicities. The term ‘internal colonialism’ was used first by V.I. Lenin and then by Antonio Gramsci as a framework to describe and explain the social, economic, and political inequalities that exist between regions within a social system. According to the process of modern colonialism, the system of exploitation between the imperial metropolitan state and that of the colonized nation is enforced; whereas in internal colonialism, an exploitative power relationship is created between the periphery [regions] and the core [the administrative metropolises].

Internal colonialism results from a spatially unequal wave of modernisation throughout the national territory which produces comparatively developed and less developed communities within the nation-state itself, as Michael Hechter argues. This leads to an unequal distribution of resources and power between the two groups. According to Hechter, from this moment on, the top group or the core strives to maintain and maximise its lead through measures to institutionalise the current hierarchical order. Part of this process involves regulating the distribution of highly authoritative social and political roles among institutions, communities, and regions that have been identified as members of a core group (by the core itself). A layered system is consequently produced and reproduced, which is characterised by a cultural division of labour that promotes different ethnic identification processes between two groups (and within them). The inner space of submissive and enslaved colonialism of marginalised groups generates prosperity in favour of areas and communities that are to be more closely linked to the core or centre of power and thus to the state itself. According to Hechter, what is closest to the centre is not often defined by geographical distance, as neighbouring cities and areas are often not distinguished by different treatment within nation-states based on religion, language, ethnicity, and culture. However, this approach might also be used to characterise disparities and inequalities in regions and within the state.

In addition to direct violence against the Hazara minority group, this study examines the violence perpetrated by the core against the periphery of Hazarajat (home of the Hazaras in Afghanistan) from the perspective of internal colonialism. An understanding of the Hazarajat as an internal colony of the core of Kabul would be essential to understand why the continued use of direct violence has stripped Hazaras of political and social hegemony in the Afghan government.

Identification of Hazaras

The ethnic and religious landscape of Afghanistan is difficult to explain because of its complexity. To facilitate this explanation, Sayed Askar Mousavi compared Afghanistan to a Chinese box, filled with a series of smaller and smaller boxes. Inside the boxes of Afghanistan are different ethnic groups like the Hazaras and Nuristanis. Afghanistan is recognised and understood as a heterogeneous society that includes Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Aimaqs, and other ethnic minorities. Each of these ethnic groups shares a common family ancestry, homeland, memory, possibly religion, and a sense of national solidarity. Their identities are often being made as an outcome of interconnections and ties with other ethnic groups. Each of these ethnic groups identifies themselves in a certain way; that is, subjective and objective self-perception can contradict one another.

By and large, Hazarajat was perhaps the least fortunate place in Afghanistan, the lack of social, political, and financial opportunities, combined with an ever-changing security situation, prompted the relocation of millions of Hazaras to various locations within Afghanistan as well as in the neighbouring countries. The Hazaras are generally divided into clans depending on their areas of origin, such as Behsudi, Ghaznichi, and Oruzgani. In this ancestral division, the Hazaras were then strictly divided between the Twelver or Jafri and the Ismaili.

In any case, there has been speculation over the past few centuries regarding the origin of Hazaras in Afghanistan. The myths about the historical roots of the Hazaras were introduced by J.P. Ferrier, a French explorer who visited areas of Hazarajat in the first half of the 19th century. Perrier believed that Hazaras had been in the area since the time of Alexander the Great, according to Greek writer Curtius, who claimed Alexander met people while traveling via the central route in Afghanistan; they looked very much like the Hazaras of today. The second group of historians suggested that the Hazaras were descended from Mongolian soldiers who arrived in the region in the 13th century. Bernard Dorn, professor of Oriental literature at Kharkov Imperial University, suggested that the Hazaras are Mongols descended from several Turkish tribes.

1890-1978: Oppressed region of Hazarajat

The history of modern Hazaras may be traced back to the late 19th century when Emir Abdur Rahman was in charge, but their persecution began much earlier. The contemporary era of persecution began with events in the second half of the nineteenth century. The tyranny towards the Hazara chiefs, based on the allegations that they were foreign pagans, had a lasting impact on Afghanistan’s ethnic relations and political life. To justify his abuse, the Emir rationalized the Hazara conflict by creating the illusion of Hazaras being scared of Kabul’s rulers. When the Hazaras fought against the Pashtun rulers’ armies, they exacerbated the schism between the largely Sunni Pashtuns and the predominantly Shiite Hazaras, prompting Sunni clerics to issue fatwas (religious judgments) declaring the Hazaras to be pagans. This led to an exodus of the Hazaras to Quetta in modern-day Pakistan, Mashhad in Iran, and other parts of Central Asia. Those who stayed behind and did not pay their taxes were tortured or killed. The Emir supported the rejection of the Hazaras in the region, allocating undeveloped land to the Pashtuns and facilitating their settlement in the area. Several kings came and went, all of whom regarded the Hazaras as second-class citizens and supported the right of Kuchis (nomads) to the lands in Hazarajat. In the 1970s, the monarchy was overthrown and Afghanistan’s first president, Mohammad Daoud, assumed control. The new republic of Afghanistan continued to ignore the exploitation of the Hazaras at the hands of the Kuchis and forced the Hazaras to migrate to urban centres such as Mazar-e-Sharif and Kabul to escape the poverty of the Hazarajat. The institutional oppression and direct violence that made Hazaras extremely vulnerable during the 1970s resulted in social and political marginalization during the USSR invasion of Afghanistan.

1978-1996: Chaotic Situation During and after the Invasion of Soviet Union

President Daoud Khan’s tenure was short-lived, as a communist coup deposed his administration in April 1978, and the Peoples’ Democratic Party of Afghanistan, led by Nur Mohammad Taraki, took control. The movement, known as the Saur Revolution, swiftly sparked widespread insurgency and civil war in Afghanistan. During the Soviet invasion, the Hazaras hailing from the Hazarajat liberated the region from Soviet aggression, making it a non-autonomous state in the 1980s. Following the Soviet occupation, numerous anti-communist resistance groups adopted the name ‘mujahideen’, which means ‘holy warrior’ in Arabic. The Hazaras were expelled from their homeland by the Communists, but instead of bringing peace, Shiite anti-communist parties ended up fighting. Following the failure of the invasion, Afghanistan’s communist-backed President, Dr. Muhammad Najibullah, had to resign in April 1992, shortly after the disintegration of the Soviet Union. After the Soviet war in Afghanistan, the Khazarian fighter Abdul Ali Mazari, with active Iranian support, managed to unite the Hazaras and the Shiite groups fighting for control of Hazarajat under the banner of Hezbe-e- Wahdat: The Solidarity Party. Two presidents were appointed briefly in the meantime, but none of them could control the aggravating situation of the country. Fierce fighting broke out between the ISA camp and the army in Kabul. On 11th February 1993, 750 Hazaras civilians were killed in the Afshar massacre in western Kabul. ISA troops and the Pashtun warlords of Abdul Rasul Sayyaf attacked Afshar, killing 7,080 people on the streets.

Internal marginalisation followed by direct violence was a recurring theme throughout the Soviet and post-Soviet eras. The post-withdrawal time was chaotic, with several governments being around, but the conditions and misery endured by Afghan minorities did not improve, and the years that followed were even worse for them when the Taliban came to power.

1996-2001: Persecution of Hazaras

In the turmoil and brutalities of war, the Taliban emerged as the ruling party, and the situation turned out to be an ordeal for minorities. When the Taliban took control of Kabul in 1996, they convinced Abdul Ali Mazari, also known as Baba Hazara, to organize a meeting with them, which resulted in him being arrested and killed along with several of his closest companions. The slogans used by the Taliban for Hazaras were offensive and derogatory, giving complete freedom to the rest for the persecution of Hazaras.

“Tajikistan to Tajikistan, Uzbekistan to Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan to Turkmenistan, Hazaras to Iran or the road to the cemetery is Afghanistan” or “Hazaras are not Muslim. You will slaughter them. This is not a sin,” said Taliban governor Mullah Manon Niyaji.

In 1998, the Anti-Taliban’s Northern Alliance occupation of Mazar-e-Sharif was abruptly ended and Taliban troops entered the city, leading to a bloody uprising that killed about 2,000 people, mostly Hazaras civilians. Human Rights Watch said the “second massacre at Mazar-i-Sharif was one of the worst atrocities in Afghanistan’s long civil war”. In addition to the 2,000 dead, more than 4,500 people were arrested and detained for months while hundreds escaped to the neighbouring districts in the rain to avoid rockets and airstrikes. Two years later, around 8th May 2000, another massacre of civilians occurred in Khazar near the Lobatak Pass, north of the city of Bamiyan.

The Taliban’s five years in power were marked by direct violence, massacres, and human rights violations, yet a handful of people supported minorities like the Hazaras in their fight against the administration of the Islamic Emirates of Afghanistan. The terrorist attacks of 11th September 2001, and the Bush administration’s decision to eradicate al-Qaeda from Afghan soil have been heavily criticized, but these actions appear to have saved the lives of the Hazaras

- 2016: Era of international interventions

With the fall of the Taliban government and the beginning of an era of international intervention, the minority groups were thrust into a time of structural violence inflicted by the rulers’ colonial minds. The Bonn Agreement served as a roadmap for the transition of the state into a multi-ethnic, gender-sensitive, and fully representative Afghan government by the preamble of the agreement. In the upcoming years, the process of the DDR, or disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration, as well as the permanent constitution will be worked out within the given time frame. The first transitional government consisted of 11 Pashtuns, 8 Tajiks, 5 Shiites / Hazar, 3 Uzbeks, and 2 other minorities. Hamid Karzai was elected Chairman of the interim administration by the Emergency Loya Jirga, as well as being Afghanistan’s first democratically elected president in 2004 and again in 2009.

Some things have remained unchanged over the years, such as ethnic politics and escalating structural violence against minorities, especially Hazaras. In the post-Taliban era, the inclusive concept of government aimed at alleviating ethnic divisions inadvertently led to greater ethnicization in politics. The Bonn Agreement created a formula of ethnic hierarchy that led to the formation of ethnicity as a political factor in the Afghan system. First Vice Presidents Ahmad Zia Masood and Qasim Fahim were Tajiks, while Karim Khalil, who served as the leader of the Hezb-e-Wahdat, was the second Vice President of 2004 and 2014. Ethnic representation was thus reduced to the distribution of offices without addressing the underlying sources of ethnic politics in the state. The Karzai and subsequent governments recognise minority rights, at least on paper, but most governments and international community funds have been transferred to more powerful ethnic groups like the Pashtuns or Tajiks, or more accessible cities like Kabul, Herat, and Mazar- e Sharif. Lack of investment and continued discrimination resulted due to the increased structural violence against minorities in the state

The Socio-Economic condition of Hazaras post 9/11

The situation in Hazarajat has been dire since Afghanistan’s independence. Years of fighting, oppression by the Taliban, and famine have severely deteriorated this naturally destitute region, destroying most of the country’s fundamental development and economic activity. There was a lack of proper sanitary conditions and drainage channels, healthcare services, school buildings and supplies, well-trained teachers, drinking water, workplaces, and decent roads in Hazara-dominated districts. The two districts dominated by the Hazara population were severely affected, namely Qarabagh and Bamiyan. Qarabagh was indeed very poverty-stricken, with inadequate toilet facilities and sewage systems, only one run-down hospital with 36 beds, 3% of households with no earnings, and a literacy rate of 35%. Bamiyan’s provincial profile, like that of Qarabagh, has gone through the worst of times. Bamiyan was regarded as one of Afghanistan’s poorest and least lucrative agricultural areas, with severe malnutrition and a lack of adequate school facilities. Even though a heavy amount of money was coming into Afghanistan through international aid in 2009, the Hazaras were regarded as the poorest ethnic minority in the country. Despite the Hazaras’ desire to seek higher education and improve their social and financial condition, they received little assistance. Instead, the Hazaras attempted to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, seizing new chances in education and work. A significant minority population passed college entrance exams and enrolled in higher education, with Hazara girls surpassing other genders and ethnic groups.

These are just a few examples of how the Hazaras have been denied their basic rights such as access to education, food, and shelter. Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner sparked worldwide interest in the plight of Hazaras and how its fanaticism is taking root in Afghan society. The novel contains frequent references to Hazara prejudice, such as being labelled “mice-eating, flat-nosed, load-carrying donkeys.” Hazaras, who have been stereotyped as aggressive and repulsive, resisted their oppressors, which exacerbated the atrocities inflicted on them by every government.

Hazaras under the National Unity Government

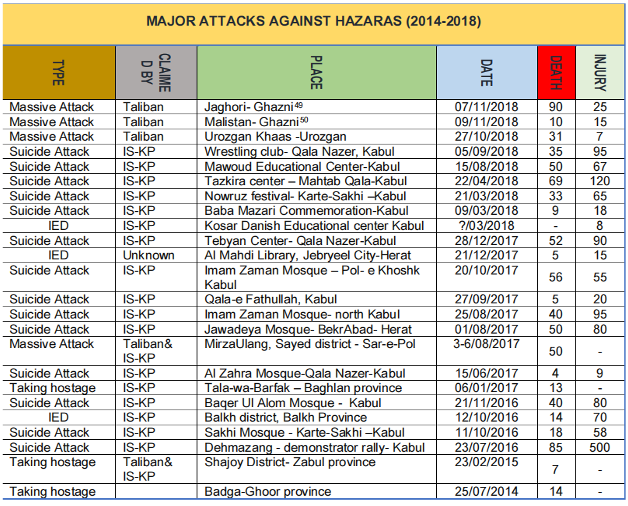

Following 9/11, the Taliban intensified their attacks on non-Pashtun places. To consolidate authority over the areas inhabited by Hazaras, the Taliban launched direct and indirect attacks on virtually every area in Hazaras. Since the National Unity Government took control in 2014, the Hazaras have faced adversity due to direct and structural violence. Not only have the Taliban stepped up their attacks and turned their attention to the Hazaras region, but the Islamic State of Khorasan province ISKP has committed atrocities on public locations such as educational institutions, mosques, religious gatherings, and rallies. The following data shows attacks by the Taliban and the ISKP against Hazaras.

The state of the Hazaras has always been precarious, whether with foreign intervention or during the democratic administration of the National Unity Government, but now that the United States has withdrawn the most pressing concern is what the future holds for minorities, especially Hazaras.

Is the future bleak or bright?

To build an inclusive administration in Afghanistan, the Taliban accepted members of minority groups into their temporary structure. Dr. Muhammad Hassan Gaysi was sworn in as the Afghan health minister. But will these little gestures pave the way for improved relationships and acknowledgement within the state? The recent attacks on Hazaras offer little hope to Hazaras and also those seeking peace and prosperity in the state and the region. The Taliban in Kabul operate with a colonial stance, taking control and refusing to allow others to lead an independent life. As William Wordsworth said, ‘Life is divided into three terms – that which was, which is, and which will be. Let us learn from the past to profit by the present, and from the present, to live better in the future’. It would appear that when the Hazaras turn back to find direction, there is no hope for the future.

The emergence of a moderate Afghanistan, a patchwork of modernisation and extremism, and a stride reversal policy, are four possibilities that might represent the government’s approach towards Hazaras in Afghanistan. In the first scenario, the Taliban uphold all their pledges made since their arrival in Kabul. It implies that the governing Taliban act responsibly as a political player both within and outside of the state. This will not result in a progressive democratic state or a very inclusive society, but it will stamp its administration with some degree of inclusion. In such cases, the Hazaras would be given their due share of administrative responsibilities and will be able to live peacefully without fear of discrimination or marginalization. The rest of the two aforementioned scenarios will be ineffective because, if the Taliban pursue a patchwork of modernization and extremism, the Hazaras would be on the receiving end of extremism. The most likely scenario is the stride reversal strategy. In this situation, the Taliban will take steps that appear to encourage openness and inclusivity at first, giving the appearance of a steady shift toward a more moderate Afghanistan. However, after worldwide recognition and a seat in the international community as well as investments in large infrastructure and mining projects, the government would gradually restrict the political and social activities of minorities. The above possibilities indicate that the Hazaras are unlikely to be part of the core of Kabul and the colonial mindsets of the Taliban will not allow minorities like the Hazara to gain institutional authority. Throughout the years of democratic governments or Taliban regimes, the Hazaras have been threatened by direct violence and remained victims of social and political marginalization, as the colonial mindset persists. Nobody in a position of authority is willing to relinquish their power or involve others to make the system more inclusive. Things will remain static for the Hazara community which will have to make a concerted effort to ensure their survival and a better socio-economic position in their ongoing fight against oppression in a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan.

![]()

Be the first to comment