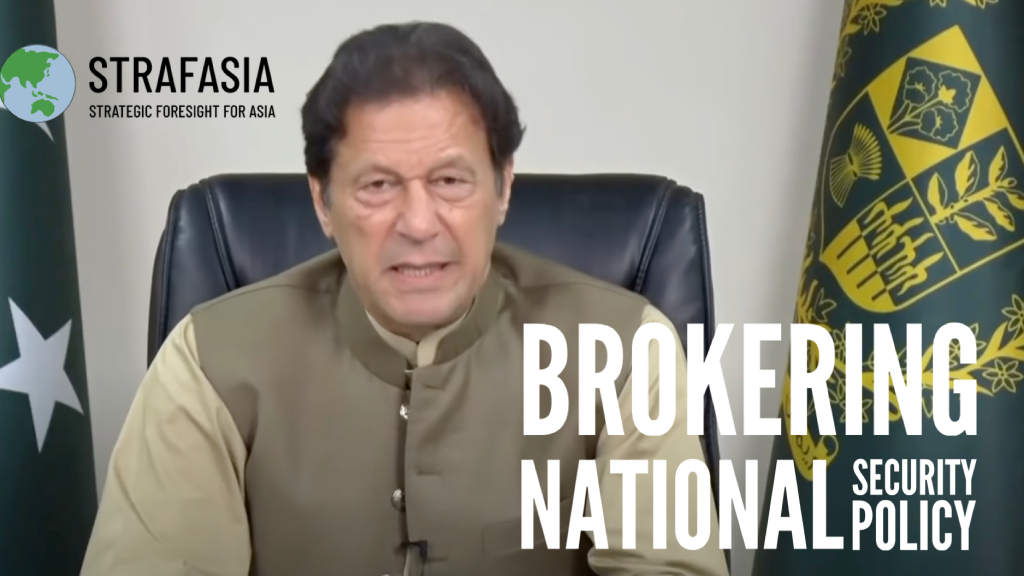

The public version of Pakistan’s National Security Policy (NSP) released by Prime Minister Imran Khan on 14th January 2022 promises a citizen centric ‘Comprehensive National Security’, which puts economic security at the core by labelling the traditional ‘guns versus butter’ debate as ‘archaic.’ Notwithstanding the assertions by the National Security Advisor (NSA) emphasizing the symbiotic linkage between traditional and non-traditional security, the NSP is likely to trigger a vibrant debate on what constitutes national security, and whether it would be possible for a country like Pakistan to shift its focus away from geo-politics and towards geo-economics by neglecting the regional and global security challenges.

The release of the NSP is a welcome step but the overzealous defense and celebrations of a document whose summary has only been released, while the major contents remain classified, could lead to false expectations. It also risks projecting the impression that there existed no policy framework in the past to prioritize national security needs; this is not true, and could create unnecessary friction amongst various stakeholders that are performing as per the mandate provided by the Constitution.

Most countries formally declare their NSP for public consumption to convey their national priorities, which are generally shaped by three main considerations: 1) what role is being envisaged for the state in the international system; 2) the challenges and opportunities; and 3) the role and responsibilities of all the stakeholders in addressing these challenges and opportunities.

Does the new NSP justify these perquisites? Pakistan may have the vision and the potential to become a regional trade hub, but it cannot overlook the challenges posed by continued instability in Afghanistan and by India’s perpetual animosity towards Pakistan. Similarly, the geo-economic vision can only materialize if the country has economic sovereignty, which at present seems gravely compromised due to the excessive involvement of international monetary institutions.

The claim that the newly launched NSP for the ‘first time’ puts human security at the core – is also misleading. National security as a concept has always been human centric, and states are the ‘means’ and not the ‘ends.’ A security policy that does not cater to its people (nation’s) needs cannot be termed as ‘national.’ According to Buzan, individual security “represents a distinct and important level of analysis”, but “is essentially subordinate to the higher level political structure of state and international system.” States “constitute the primary nexus when it comes to security for individuals and groups,… and the single most important macro-structure with consequences for individual security.” Therefore, whatever national decision makers do to strengthen state security in a democratic society, must ideally strengthen the individual’s security.

These principles are an integral part of the national security policies of most countries that have publicly released documents. The Interim National Security Strategic Guidance (INSSG) released by the Biden Administration in March 2021 outlined three main priorities: 1) to protect the security of the American people; 2) to expand economic prosperity and opportunity; and, 3) to defend democratic values.

In pursuit of these principles the US committed to:

- “Defend and nurture the underlying sources of American strength, including our people, our economy, our national defense, and our democracy at home;

- “Promote a favourable distribution of power to deter and prevent adversaries from directly threatening the United States and our allies, inhibiting access to the global commons, or dominating key regions; and

- “Lead and sustain a stable and open international system, underwritten by strong democratic alliances, partnerships, multilateral institutions, and rules.”

Similarly, the UK’s Integrated Review 2021 outlined three fundamental national interests, i.e., sovereignty, security, and prosperity. The Review also sets four objectives for the UK to pursue in the best interests of their people:

- Sustaining strategic advantage through science and technology

- Shaping the open international order of the future

- Strengthening security and defence at home and overseas, and

- “Building resilience at home and overseas

The Chinese also articulated their national security priorities in an overarching manner to meet their leadership’s objectives by introducing the concept of ‘Comprehensive Security’; it incorporates eleven different aspects of security, including political, military, territorial, economic, cultural, social, scientific-technological, information, ecological, nuclear, and resource security. These aspects have been mentioned to safeguard their political system from external influences. Interestingly, some of it has also been reflected in Pakistan’s NSP document without taking into consideration the ideological and capacity differential between the two countries.

The Chinese leadership views economic and military security as being mutually dependent. Expansion of military power is considered essential to realize the leadership’s goal of making China a global power, and to achieve this objective, a strong economy is essential. Pakistan’s NSP also makes a similar promise of a bigger share of pie for the military as and when the economy grows; but it does not take into consideration the fact that while China can choose when and how much to spend to achieve its global ambitions, Pakistan is compelled to maintain minimum conventional and nuclear capabilities that deter India from venturing into a military conflict.

Conclusion. A National Security Policy is unique for all countries and is shaped by the national power potential. Since no country has absolute power, states develop their security strategies by exploiting their strengths and to overcome weaknesses. Merely announcing a shift to geo-economics without streamlining the domestic economy or addressing institutional and structural shortcomings, can only create further confusion, besides triggering an unnecessary ‘guns Vs butter’ debate. This could also potentially make it difficult for the future national leadership to spare more resources for traditional military threats which are likely to increase due to continued instability in Afghanistan and India’s growing regional ambitions. If a workable and realistic NSP has to be negotiated, it must be in line with the existing national power potential that can address contemporary traditional as well as non-traditional security threats through the available means, and cannot merely be based on a vision which, even if desirable, could take several decades to materialize.

(The author is a co-founder of Strafasia. Views expressed by the author are his own)

![]()

Be the first to comment