South Asia is once again on a military escalation trajectory as a consequence of India’s decision to annex the occupied territory of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). Instead of taking corrective measures, senior Indian ministers are engaged in a nuclearism, and have once again hinted the possibility of giving up the nuclear No First Use (NFU) pledge – a non-binding commitment that had been a central tenet of India’s nuclear doctrine, but continues to remain under perpetual strain due to a lack of conviction amongst India’s own decision makers.

South Asia is once again on a military escalation trajectory as a consequence of India’s decision to annex the occupied territory of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). Instead of taking corrective measures, senior Indian ministers are engaged in a nuclearism, and have once again hinted the possibility of giving up the nuclear No First Use (NFU) pledge – a non-binding commitment that had been a central tenet of India’s nuclear doctrine, but continues to remain under perpetual strain due to a lack of conviction amongst India’s own decision makers.

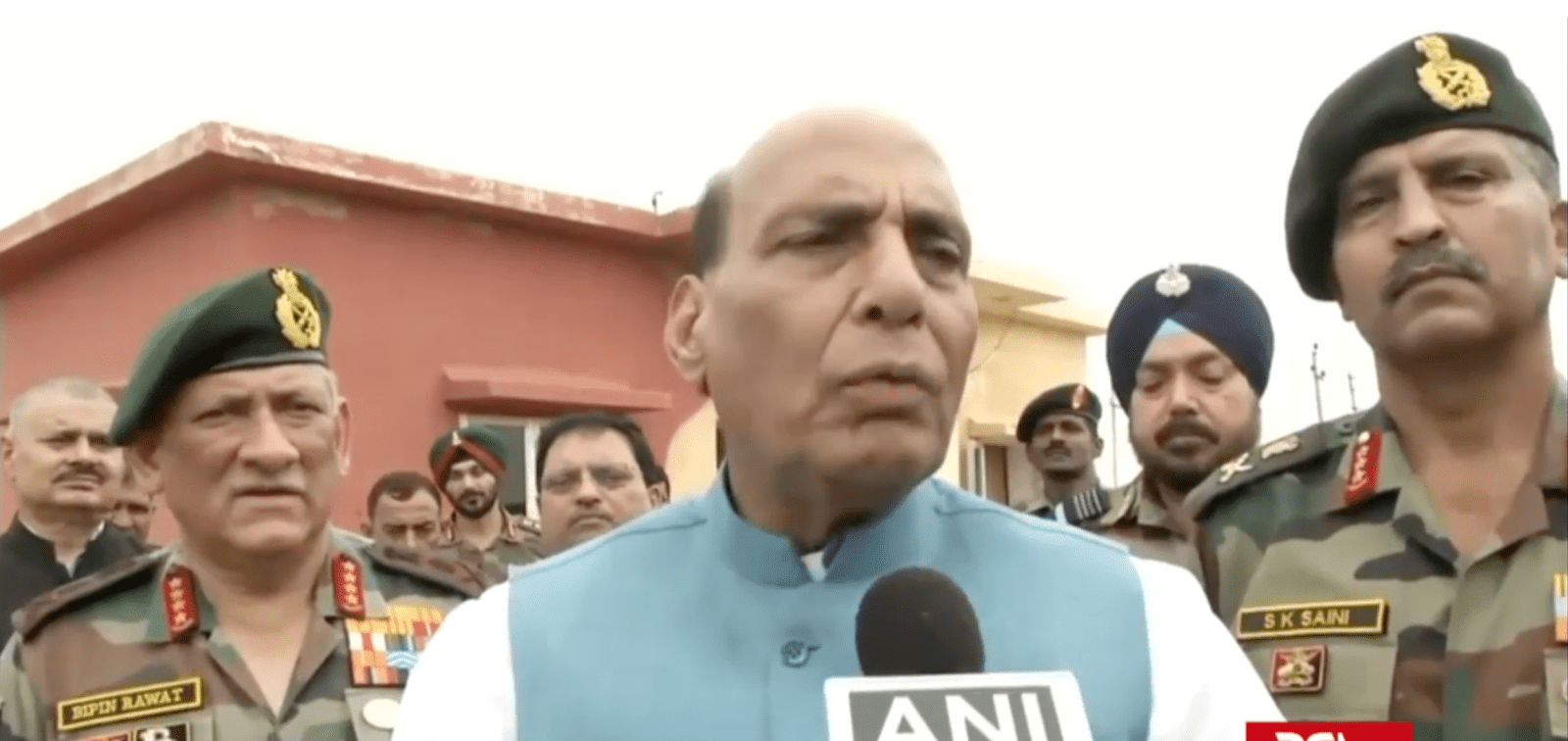

On the occasion of the death anniversary of India’s former PM, the current Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, while visiting the Pokhran nuclear test site tweeted: “…India has strictly adhered to this [NFU] doctrine. What happens in future depends on the circumstances.” This was an ominous threat directed towards Pakistan with the possibility of a pre-emptive strike – to deter Pakistan from contemplating the use of its nuclear weapons against the Indian conventional forces in a future conflict.

NFU is a declaratory position maintained by several nuclear weapon states that they will not be the ‘first’ to use nuclear weapons against their adversary. None of the nuclear states, except China, have an unconditional NFU. India’s draft nuclear doctrine released in 1999, included a commitment that it “will not be the first to initiate nuclear strike.” Subsequently, the 2003 doctrine, which became an official nuclear policy, added a caveat that nuclear weapons “can be used in response to the use of chemical or biological weapons against India or Indian forces anywhere.” It diluted the very essence of an NFU commitment and therefore lacked credibility with India’s adversaries.

The recent statement by the Defence Minister is not the first time that India’s NFU has come under spotlight. One of his predecessors, Manohar Parrikar, had also questioned the rationale for India having an NFU, but his remarks were later labelled as a personal opinion. Amongst others who have been critical of India’s NFU commitment include the former commander of India’s strategic command Gen B S Nagal and a former National Security Advisor, Shiv Shankar Menon, who wrote in his 2016 book that:

“There is potential grey area as to when India would use nuclear weapons first against another NWS (Nuclear Weapon State). Circumstances are conceivable in which India might find it useful to strike first, for instance, against an NWS that had declared it would certainly use its weapons, and if India were certain that adversary’s launch was imminent.”

The Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) leadership is known for its proclivity to make controversial statements due to party lineage rooted in Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which is a militant wing of the BJP. In its 2014 election manifesto, BJP unnerved many when it announced that after coming to power, their government will revise India’s nuclear doctrine. The election pledge was not followed through due to strong public reaction and international concern. Subsequently, PM Modi had to announce that there is no intent of revising India’s nuclear doctrine.

Can India Afford to Review its NFU? Giving up on the NFU posture could have a serious cost for India’s own security and the credibility of its nuclear doctrine. If India decided to launch a pre-emptive first strike against Pakistan, it would never be able to have the assurance that it would significantly degrade Pakistan’s retaliatory capacity, which would be enough to cause unacceptable damage to major Indian cities. In such an eventuality, Pakistan might suffer significant damage, but India will also cease to exist as a coherent society.

And, in case India decides to give up on its NFU commitment and adopts a more assertive position, but eventually fails to launch a pre-emptive ‘first strike’ against Pakistan, the credibility of its deterrence posture would become questionable.

The controversy surrounding India’s NFU posture could be a deliberate effort to maintain ambiguity on when India might use its nuclear weapons, but without officially giving up on its NFU commitment. This could allow India to reap political dividends, while simultaneously maintaining an assertive posture towards Pakistan, without perturbing China. The NFU ambiguity and threatening Pakistan with a ‘first strike’ could also be intended to create space for India’s Cold Start Doctrine (CSD), which was discredited after Pakistan’s decision to introduce tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs).

Challenging the NFU position and building an argument for a first strike also helps the BJP to build its nationalist credentials, as it did during the most recent crisis of Feb 2019, where PM Modi threatened Pakistan with nuclear weapons by referring to a phrase ‘Qatal Ki Raat’ (the night of massacre), and also mobilized missiles along the international border primarily for the purpose of signalling, but without giving up the NFU position.

Interestingly, India’s nuclear build-up to attain a sufficiency level for a potential first strike against Pakistan is in contrast with its often stated ‘minimum deterrence’ posture. It is quite possible that India may be moving towards maintaining two asymmetric nuclear postures against China and Pakistan: a minimum deterrence and an NFU pledge against China, while building the capability for a comprehensive pre-emptive strike against Pakistan.

Conclusion. The controversy surrounding India’s NFU as a result of periodic statements coming out from senior decision makers, highlights serious vulnerabilities in India’s decision-making process. Repeated iterations are likely to create discomfort amongst India’s main adversaries, especially Pakistan, which would be forced to take remedial measures and increase the sufficiency level, to ensure the credibility of its deterrence posture.

Be the first to comment