On 17th July 2019, the International Court of Justice gave its verdict on the latest legal dispute between Pakistan and India. Kulbhushan Jhadav, an undercover operative of Indian intelligence, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), was caught in Baluchistan on 3rd March 2016. Following his arrest, the military court of Pakistan sentenced him to death on 10th April 2017. India argued in the ICJ that Pakistan did not give consular access to the accused and moved for a retrial in a civilian court. Consequently, the ICJ stayed the execution, and the case hearings ensued in the ICJ.

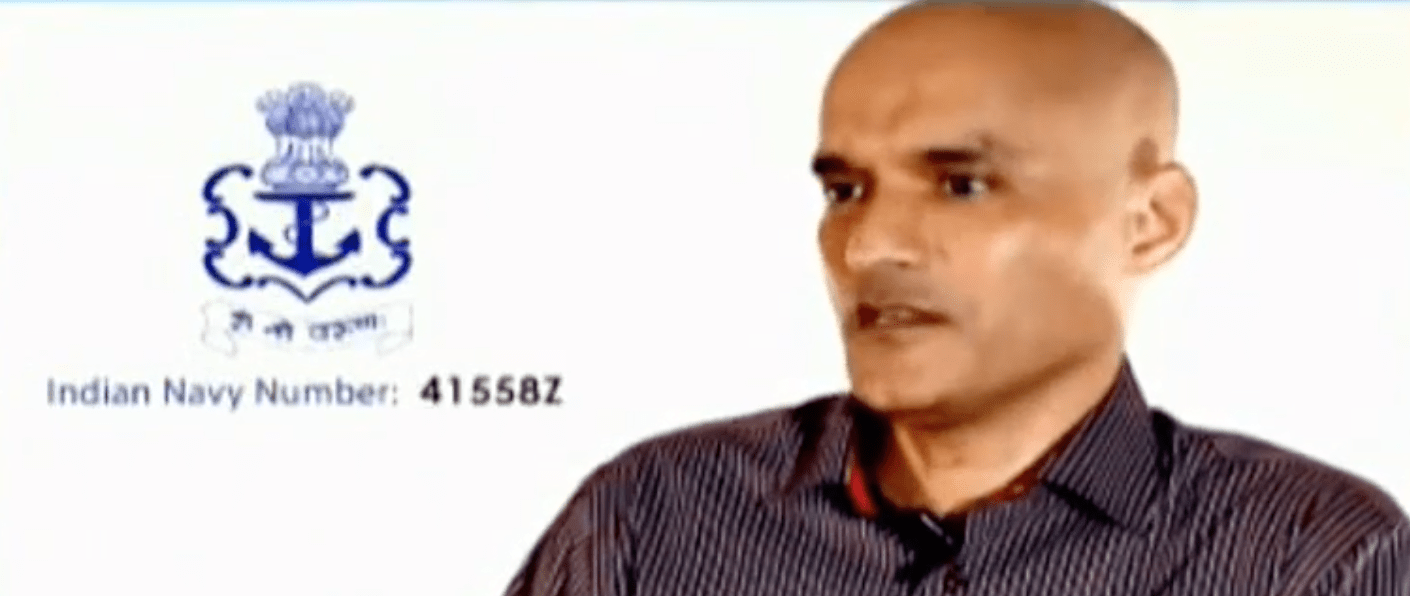

During the hearings, India repeatedly chided Pakistan for abusing the fundamental human rights of the accused, accused it of violating the Vienna Convention, and professed the innocence of Kulbhushan. Pakistan adhered to laying down the bare facts: Kulbhushan was an Indian spy operating under a fake alias and was caught while in possession of two passports; he had been involved in activities of espionage and arson in Baluchistan and Karachi, as per his own confession recorded on video. Countering Pakistan’s facts with rhetoric, the Indian side failed to refute the claim that Kulbhushan was an Indian national, holding two passports, both of which had been issued by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs.

The ICJ verdict of last week rejected, by 15 votes to 1, the objections of Pakistan for the admissibility of the Indian case in the ICJ and admitted it. Furthermore, in 15 votes to 1, the court held Pakistan responsible for not providing immediate consular access to the spy, under article 36 paragraph 1(b) of the Vienna Convention 1963. It found that Pakistan did not inform India in time, nor did it inform Jhadav of his rights under the Vienna Convention. While for India, the court ruled that the execution order must be revisited by Pakistan, but a retrial in a civilian court was not likely.

As soon as the verdict was announced, both sides proclaimed victory. But the question remains as to what becomes of Kulbhushan and where he stands now. It is an indisputable fact that he was involved in espionage activities against Pakistan, both financially and logistically. India’s diplomatic shrewdness gave it the advantage that it took the case to ICJ based on the argument of consular access under the Vienna Convention.

Pakistan respects international law and has expressed its reverence for the rule of law between states. But the case under consideration was not that of a regular civilian, but of a spy. Pakistan could have a myriad of reasons for not allowing immediate consular access. For instance, from the instance Kulbhushan was apprehended, the whole incident became a matter of national security. Providing Kulbhushan access to the Indian consulate right after his apprehension would have culminated in the transmission of intelligence, which runs counter to Pakistan’s national interest. So, it was unfavourable for Pakistan to provide such a platform to a spy.

The ICJ failed to recognize the difference between a spy and a civilian. Human rights are inalienable and indispensable for everybody, regardless of their profession; but the case at hand was between two of the most hostile countries in the world. And India’s interest in the Baluchistan insurgency is also evident. By applying the provision of the Vienna Convention to an apprehended spy, the ICJ has set the precedent of bypassing matters of national security.

But the matter of Kulbhushan returning to India is still a distant idea. The ICJ can decide a matter under international law, but it cannot compel a state to do something. It has asked Pakistan to provide consular access to the accused, which Pakistan will provide because it is obliged to do so under international law. But the ICJ cannot interfere in the internal workings of a country. It cannot declare Pakistan’s trial of Kulbhushan null and void, nor can it order it to return the spy to India, which the Indians are jubilantly stating will happen. That part of authority stays with Pakistan.

Justice is not an objective thing in international relations, and states have to adjust to unequal power distribution

-Hans J. Morgenthau

Pakistan won a strategic upper ground in the verdict, but the words of the verdict translate in favour of India. The reason for this imbalance is because of India’s diplomacy. India is on its way to becoming a major global economy, despite its share of poverty, human rights abuses in Kashmir and destabilizing activities in the region. When it comes to economy and numbers, India is way ahead of Pakistan. This factor gives leverage to the Indian cause and its activities in the international arena. According to realism, states are unequal in power, so the justice they are dispensed in the international arena is also according to their power or worth. The global standing of a state plays a great role in its transactions across the world. Currently, Pakistan is dealing with the FATF, resurfacing from terrorism, playing a part in the Afghan peace process, and has pledged forces to counter terrorism in the Islamic world especially. But the coercive diplomacy of India in international institutions is prevalent. India has been trying to secure a permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council, while repeatedly asking the permanent members to revoke Pakistan’s membership of the UN and declare it a terror state. But Pakistan’s friends, such as China and Turkey, have supported it on various occasions.

As far as Kulbhushan is concerned, he will remain in Pakistan’s custody because of his activities against the state. Pakistan will comply with the ICJ’s ruling of staying the execution order, but that does not imply that it will not happen in the future. Because Pakistan’s law, where it emphasizes the provision of fundamental rights to all humans, also has death penalty embedded in it. Suffice it to say, article 3 of the constitution of Pakistan sums it up in this manner:

“…from each according to his ability to each according to his work.”

Be the first to comment